Sam and Mary (Mankus) Lapinski (Lapinskas) behind the bar, 1935

Family-owned corner taverns where coal miners ate, drank and socialized proliferated throughout Springfield during the first half of the 20th Century. Keeping the tavern going was a family affair, with wives often doing the cooking and cleaning, and husbands, sons and sons-in-law tending bar. This leads me to believe that a goodly number were founded by formerly single miners after they married as a step up the economic ladder–and like the corner grocery store, a safer line of work. The tavern family usually lived behind, above, or next-door to their establishment.

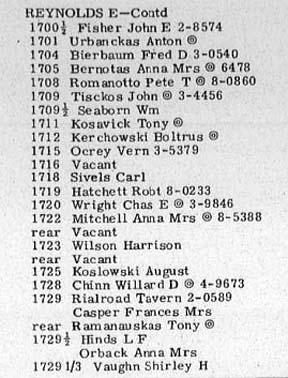

The following local taverns, most now defunct, were owned by Lithuanian immigrants and/or their offspring: Lapinski’s (11th & Washington), Bernie Yanor’s and Jim Casper’s taverns (opposite corners of 11th at Peoria Rd.), (Kostie) Welch’s Tavern (11th and Laurel–later at 1827 Peoria Rd.), The (Rekesius) Welcome Inn (11th and Washington), Tony Romanowski (Antanas Ramanauskas)’s “The Railroad Tavern” at 1729 E. Reynolds, “Alby’s” (and Vera Stasukinas’) Tavern (14th & Carpenter), Bozis’s tavern on E. Mason, Enoch and William Blazis’s White City Tavern on E. Cook St., Carl Pokora’s tavern at 22nd St. and S. Grand Ave. East, The Lazy Lou at 1737 E. Moffatt, not far from Pillsbury Mill, which was owned by Frank W. and Mary (Gerula) Grinn–plus taverns owned by Walter Kerchowski (“Wally’s”), Nancy (Kensman Zakar Nevada) Treinis around 16th and Carpenter and Anna (Leschinsky) Kasawich on E. Reynolds St. I’m sure there were even more.

Back row, l to r: Antonia and Bernie Yanor, owners of Bernie’s tavern, with daughter Josephine (Stankavich). Front row, l to r: Yanor children Joe, Anna (Carver), and Bernie, Jr. 1920s.

Some taverns started out serving beer to miners in the early 1900s, then became grocery stores or soda fountains, exclusively, during 1920s Prohibition–then reverted to taverns again in the 1930s. The ancillary restaurant/grocery functions of taverns were perhaps not as important as their provision of alcohol, but many are still also remembered for their food. Fish dinners on Friday were extremely popular, due to a heavily Catholic customer base. An ad from 1956 for Alby’s Tavern mentions “Homemade Chili, Hamburgers, Hot Tamales and Cheese.” In 1940, Welch’s Tavern had chicken and potato salad dinners for 10 cents and boneless fish dinners for 5 cents.

The Fairview as it is today, under different ownership

Over the decades, the basic tavern “hole in the wall” with food and drink evolved into the larger and more ambitious “supper club” that featured entertainment such as live music with dancing and a more extensive–and expensive–menu for sit-down dining, drawing customers from a wider area. One of the first of these was The Blue Danube, built on Keys Ave. by the Yates/Yacubasky family in 1933. Some of the best-known Lithuanian-owned supper clubs were The Cara-Sel Lounge (Tony Yuscius) on N. Grand Ave., the Skyrocket Inn (Kostie Welch) on Sangamon Ave. near the fairgrounds, The Fairview (Alex & Alice Palusinski) and Butch’s (Frank Gudauski’s) Steak House on Sangamon Ave. east of the fairgrounds, Boggens Grove (Harmony House?) on West Washington, (Stephen) Benya’s Supper Club in Nokomis, and the upscale Saddle Club (Joe Welch) at 307 S. 6th St., which was also a local newspaper watering hole.

Lapinski family, 1940s?

Taverns served an important, little-known function during the infamous “Mine Wars” 1932-35, when they were neighborhood “commissaries” for striking members of the Progressive Miners of America (PMA), storing and distributing food to hungry families. A Dec. 4, 1937 article in the Illinois State Journal describes character testimony given by Lithuanian-born tavern owner Sam (Simon) Lapinski in defense of Sam’s Lithuanian-American son-in-law Anthony Chunes, who was on trial in federal district court in Springfield for strike-related railroad sabotage. The article states that Anthony had been a bartender at Lapinski’s, and that the basement of the tavern functioned as a PMA commissary. Chunes was convicted and imprisoned in the 1937 mass trial of 36 PMA strikers, despite the testimony of his Lapinski wife Monica (they later divorced), father-in-law and mother-in-law. (Lithuanian-Americans Charles Mostaka and his son-in-law Joe Biernoski testified in defense of PMA miners Sam and Tony Profeta in the same mass trial.)

Distributed, as they were, throughout Springfield’s neighborhoods and built on an intimate scale, corner taverns were the neighborhood restaurants and entertainment centers of their time: an era when social life took place on the scale of the family and the neighborhood, and “people knew each other.” They were the familiar and common places for adult socializing, listening to juke box music, and playing pinball, shuffleboard, punch boards and slot machines. On the bad side, taverns presented a temptation to alcohol and gambling (both during and after gambling was legal) on every corner for those who could least afford it. To my knowledge, the potentially rougher side of tavern life made them generally off-limits for children at night.

Punch boards were a form of gambling in which a key was purchased and used to push in a circle on a board to see if there was a prize behind. During the height of the Depression, before gambling became illegal within Springfield’s city limits in 1939, even candy stores had punch boards with candy prizes for children. The price of the key was commensurate with the value of the potential prize.

One family of Lithuanian-American tavern-keepers was prominent in the business of distributing punch boards to taverns and social clubs throughout the county for decades, according to primary source and newspaper reports. In sensitivity to the illegal nature of the business in the city after 1939 and the county after 1948 (more of less), a descendant of that Lithuanian-American family has emphatically requested that I not write about the family’s great success in this aspect of the tavern business.

Therefore, I can only refer any interested readers to several articles in the Illinois State Journal. One, dated Oct. 21, 1948 gives the names of Sangamon County’s three main punch board suppliers according to a special grand jury report. Another, dated Sept. 6, 1963, describes gambling arrests related to a raid by authorities on a (non-Lithuanian-owned) tavern called The Press Box. A March 12, 1964 Journal article describes an anonymous tip and police raid on a garage behind a Lithuanian-American tavern on Peoria Road that netted 5-10,000 punch boards and tip boards–and resulted in a family member’s arrest.

Growing up in a Tavern Family

N. 11th St. near Peoria Rd. building where Klim’s Shoe Repair was located and Klim and Yanor-Carver families lived

And now, for the perspective of a Lithuanian-American girl whose family was in the tavern business, we have the memories of Georgeann (Carver) Madison, granddaughter of Bernie and Antonia Yanor, owners of Bernie’s Tavern. In early childhood, Georgeann lived with her parents George and Ann (Yanor) Carver above Lithuanian immigrants Peter and Helen Klim’s Shoe Repair shop, next door to Klim’s son Jim Casper’s Tavern, and across the street from Bernie (Yanor)’s Tavern.

little Georgeann Carver (of the Yanor clan) in a home-made “swimming pool,” 1940s.

Georgeann recalls: “My Uncle Bernie tended bar there and after school, I was allowed to sit at the end of the bar and watch “Pinkie Lee” on TV instead of practicing my piano lessons like my mother sent me across the street to do.” (Before TV ownership was common, television was another major draw of the corner tavern. In 1956, an Alby’s ad enticed customers to come in and “Enjoy Television Tonight”).

Georgeann continues: “My Uncle Bernie cooked the best cheeseburgers, tamales, chili and barbecues. He would make a cheeseburger for me even though my mom wanted me to eat dinner at home. Almost every time I was there, my grandfather would hand me a silver dollar out of his pocket. I would be at the tavern in the early evening before the coal miners came in from work at the mine on 11th Street.”

George and Anna (Yanor) Carver, baby Georgeann Carver (Madison), circa 1945

She also remembers that on Christmas Eve, Father Stanley Yunker, pastor of St. Vincent de Paul’s Lithuanian Catholic Church, would come to the Yanor living quarters at the tavern and distribute Holy Communion. “He would have a drink of whiskey or wine or two and some holiday food with the Yanor-Stankavich-Carver families.” (Georgeann’s beloved maternal aunt Josephine Yanor and husband Bill Stankavich lived across Peoria Rd., one block south on 11th St.)

Here are some additional memories from Georgeann, Sharon Darran, Chuck Tisckos, Ann Traeger, Scott Welsh, Joe Turasky, Frank Mazrim and Bill Cellini, Jr.:

Lapinski’s: Adolph Kelert and Sam Lapinski, Jr., also a Springfield policeman, ran the tavern after parents Sam (Simon) and Mary Lapinski retired. The St. Vincent de Paul Church choir used to go there for beers and fish dinners on Friday nights after choir practice. Constance Kelert, Adolph’s wife, was a talented soloist in the choir when she died suddenly at age 44 while attending a funeral in LaSalle. During the 1940s, customers would drive up, buy carp sandwiches and eat them in their cars.

Sam, Jr. and his wife had a house on Lake Springfield, and St. Vincent de Paul’s held its annual “didelis iškylą,” a.k.a. big picnic, there in the 1950s-60s, according to Chuck Tisckos. Simon (Sam, Sr.’)s brother Jurgis Josef Lapinskas was in Central Illinois for awhile, but his branch of the family moved to Michigan to find better jobs in the early 1920s.

Sam and Mary also rented apartments in the neighborhood, including above their tavern, to World War II Lithuanian displaced persons or “DPs,” including the Abramikas family.

The Fairview: Some of the St. Vincent de Paul choir members would go there for the fried chicken (half a chicken) special on Thursday nights. Alice Palusinski was the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants Kaston and Caroline Compardo Stockus. Ownership changed when the Palusinskis retired in the 1980s, and the establishment recently re-opened after a fire two years ago.

Bouser Viele also owned The Fairview in 1956, according to an ad in the St. Vincent de Paul Jubilee book.

The Saddle Club: Owned by Joe Welch (Wilcauskas) who also, at various times, owned the Capitol Food Market, Raydine Corp., Empire Hotel and Independent Novelty, Co., according to articles in the Illinois State Journal.

Also owned by Al Miles (Milkouskas?).

The Welcome Inn: Great 5-cent fish sandwich. Part of a three-lot property owned by immigrant John Frank Rekesius, Sr.

Boggens (Bogden’s) Grove (Harmony House): A huge establishment with music and dancing. Picnics were also held on the grounds.

Bernie’s: Antonia Yanor cleaned the tavern at night, but never entered the premises during operations. The Lithuanian-born daughter of Michael and Margaret (Shalunas) Razuskinas, Grandma Antonia was introverted and spoke only Lithuanian. Her son Bernie was affected by polio and never married. Son Joe was a welder and married Monica (Monty) Yanor, a long-time officer of the Springfield Lithuanian-American Club.

l to r: Monty (Monica) Yanor, Georgeann (Carver) Madison, Josephine (Yanor) Stankavich, 1962.

The Skyrocket: Opened in 1945 by Kostie Welch (Wilcauskas), the Skyrocket started with dancing on Sunday nights to the music of The Rocket Trio, and later featured dancing every night except Monday and “really good” steak dinners, according to one ad. (Starting in 1953, Bill Cellini, Sr. had gigs playing piano at the Skyrocket with his uncle’s band.) After Kostie Welch, the Skyrocket was owned by Ules Rose, whose daughter Barb married Charlie Foster, Jr., the son of Charles, Sr. and Ann Mosteika Foster, the long-time music director and organist at St. Vincent dePaul’s Church.

Peter Welsh bought the SkyRocket in 1963 from Ules Rose. All seven Welsh children and their mother Barbara worked in the bar at one time or another, and its position next to the Illinois State Fairgrounds attracted a cast of characters few places in town would see. According to son Scott Welsh, “It was an interesting education for all of us. The stories of the SkyRocket are legend, including visits from the Hell’s Angels, dignitaries hanging out late night, and many ‘disagreements’ between patrons handled with flying fists. My dad Pete ran a tight ship and was respected by most for not putting up with a lot of problems.”

The SkyRocket served food until the late 1960s, then only during Fair week, when Barbara Welsh ran the kitchen. Thornton Oil purchased the land in the early 1990′s.

The Blue Danube: Founded in 1933 by the Yacubasky/Yates family next to their grocery on Keys Ave. The tavern was managed by Joseph Yates, as his brother William presumably spent the majority of his time in Republican politics. The Blue Danube had a kitchen, a dance floor that was “well sanded and waxed,” and an ample area for tables and booths–but its claim to fame was its “magic bar.” One State Journal-Register writer described it as “electrically charged in such a way that when specially-treated glasses are placed on it, they are illuminated in many colors. This gives the appearance of nothing short of magic, and has proven a very popular source of entertainment.”

The Blue Danube’s motto was, “where courtesy prevails,” and it featured festive New Year’s parties and Sunday dinners of either roast young duck, fried, milk-fed spring chicken, T-bone steak, frog legs, breaded veal cutlet, or roast loin of pork with many different sides, including “Chinese” celery salad and lime and grapefruit salad, plus a full spread of desserts—all for just 65 cents. Also on the menu were “fancy mixed drinks, the finest of wines, liquors and beer, good music and dancing.”

The Yates’ were involved in protracted dispute with the City’s liquor board for allegedly operating without a liquor license, hosting dancing without a permit and serving alcohol after hours. They sold their supper club in 1938. (Please see my blog post on the political rise of the Adams and Yates families).

Bozis’s Tavern: Owned by Tony and Mae Bozis, who lived next to the tavern on E. Mason in a small brick bungalow. Several Lithuanians lived around there, and across the street on the corner, Tony’s mother owned a grocery store. Sharon Darran recalls going to a celebration at the tavern after a funeral, and being served the hot Lithuanian spiced honey and whiskey drink viditos, and lots of Lithuanian food. Tony was also a plumber with his brother John, who lived in Riverton. At Bozis’s, beer was served in glass jelly jars. They had a couch in the bar and Tony would lay on it and take a nap while his wife Mae did the bartending.

Casper’s: Still standing– now “Dude’s Saloon.” Helen Klim, mother of owner Jim Casper, used to make the best chili. Klim’s shoe repair was just north on 11th Street from the tavern, which was at the corner of Peoria Rd. and 11th St.

Alby’s: Alby Stasukinas, a former coal miner, was born in Springfield, the son of Joseph Adam and Rose Anna Poskevicius Stasukinas. The tavern served a chicken lunch.