The book “We Thought We’d Be Back Soon” contains 18 oral histories of Lithuanians who became war refugees between 1940 and 1944. Next month, my review of “We Thought…” will be published in the English-language monthly, Draugas News. Please read below for the third and last in my series on this wonderful book.

Lithuanian choir, Wehnen ‘DP’ Camp, Germany. Courtesy of Pijus Cepulis Collection, dpcamps.org

‘Little Lithuania’ in the Displaced Persons Camps

Almost every refugee in this book recounts the sudden and remarkable flowering of Lithuanian culture and education–including schools, drama troupes and choirs–as soon as war refugees sorted themselves into their own national groups within the system of post-war “displaced persons” camps. What is truly remarkable is that these feats of national and cultural assertiveness occurred literally as soon as the camps were organized.

Lithuanian elementary and high schools and Lithuanian Scouts with hand-sewn uniforms were already appearing the same month that the war ended, in barracks where food was still scarce and shelter primitive. What could this be except Lithuania re-created by refugees with nothing left but their passionate desire to return home soon?

Certainly Germany was not home, but its postwar camps were an immediate collection point for those only recently exiled: the closest spot in time and space to home, where atomized individuals could reunite in their major expression of communal desire.

Of course, it helped that so many of the exiles were leading Lithuanian academics, educators, and cultural figures. One can imagine them living and organizing by their wits in a place where they are not entitled to anything but the most basic sustenance–and almost everything has been consumed by war.

One dollar, Lithuanian camp currency, Scheinfeld, Germany camp administered by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Courtesy of icollector.com

Yet educator Jonas Kavaliunas tells us that a Lithuanian school already had been organized by May 10, 1945, in the Freibug camp(s), and the same month, in Tubingen. He details the printing of one of the first Lithuanian grammar texts in Stuttgart in December 1945—as well as the difficulty of obtaining paper, ink, and a functional printing press for the job. “The idea (of organizing schools in the camps, where hunger was a daily experience), was that returning to Lithuania in a short time, our children wouldn’t have lost a year (of schooling).”

Joana Krutuliene recalls, “All of that activity was so vibrant, people were exceptionally creative. Having nothing, really, they were capable of doing, working, acting in concert…establishing schools…The artistic ensembles (choirs and drama groups) made us feel alive, united us in some way…Such a vital life, such a desire to survive, to be active.”

Conflicting Views of the First Wave

It is also in the camps that many “DP”s have their first encounters with Lithuanian-Americans of, or descended from, ‘first wave’ immigrants (who had arrived 1880-1914). Usually these are only passing mentions of help from Lithuanian-American priests, Army translators or common soldiers.

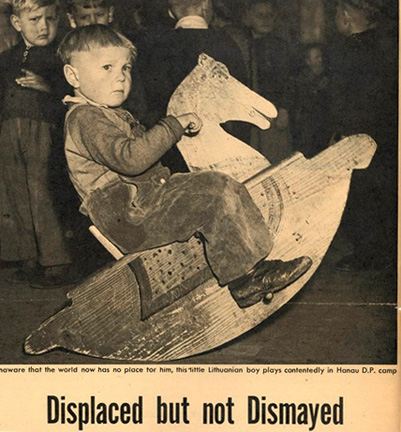

Lithuanian ‘DP’ child on wooden rocking-horse in Hanau, Germany camp, 1947. Clipping courtesy of Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Chicago.

Once in the United States, many of the same “DP”s complain of “first-wavers” from a more primitive Lithuania who don’t understand them or the more advanced Lithuania from which they have come. The farmer Taoras tells of “a good-hearted man of the old emigration” who helps him advance at work in Chicago–to the point where all the other “first-wavers” on the job burn with envy. (My father had a similar experience when he improved himself too fast for his American-born first cousins.)

Yet almost every refugee in this collection ultimately is sponsored by a member or descendant of the Lithuanian “first wave” under the U.S. Displaced Persons Act of 1948, from which the shorthand “DP” derives. Krutuliene sums it up best when she says, “I appreciate (those) Lithuanians…so much because when we got here, there was already something here for us: there were parishes already, churches already. Their Lithuanian heritage had survived, and I regret that somehow we didn’t end up making very much of a connection with them.”

Whatever their differences, the “DP” (“second wave”) immigrants did build on the institutions of the first. Their tremendous post-settlement achievement in building dozens of “heritage” schools, choirs, dance ensembles and summer camps was based in already-established Lithuanian Catholic parishes. It was from this “first wave” base that the “DP”s preserved and passed on the great cultural revival of newly independent Lithuania (1918-1940) they were a part of before being displaced.

Starting Over in America

In many ways, we can think of the flowering of “DP” heritage institutions in resettlement as an echo of that passionate, first flowering of Lithuanian culture in the camps. By the late 1940s, the camps were being dismantled and it was time for those who had united in creative, communal striving to be dispersed around the world to re-start their lives from nothing but hard work. Certainly this campaign of resettlement from post-war Germany was preferable to any forcible return to the refugees’ Soviet-controlled homeland.

However, it dispersed people who had just reunited as a national community and who wanted more and more passionately to remain together, as a national group, the clearer it became that they could not “go back soon.” As a result, in the short term, resettlement seemed to me a second diaspora even sadder and more radical than the first, tearing apart friends and even families who had somehow managed to stay together while fleeing Lithuania or to reunite in tremendous cultural enterprise in the camps.

Many separations were due to the rules of immigration or refugee sponsorship in the host countries. For example, my father was separated from his brothers and sister to arrive alone to a sponsor in Springfield, Illinois. In the book, there is the story of a female Lithuanian doctor who has to leave her handicapped daughter in an institution in Italy in order to immigrate to the United States (after being able to keep her daughter with her through the entire flight from Lithuania and her time in the camps.)

Lithuanian ‘DP’s arriving in Australia. Copyright Western Australian Museum.jpeg

Furthermore, without anything like their first geographic “collection point” in Germany, this second dispersal and permanent resettlement of refugees in the U.S., Canada, Australia, Great Britain, and South America required “DP”s to create their own new “collection points.” Geographic dispersal as a result of host nations’ immigration and sponsorship rules–as well as more local work, career and housing conditions–was a formidable centrifugal force.

Yet even without all or most of their peers from the camps–and with less time and energy due to the demands of constant work to support themselves and their families without even the primitive support once provided by the camps—the “DP” refugees still managed to build new “Little Lithuanias” all over the world.

Lithuania’s ‘Greatest Generation’

I don’t know if this makes the “DP”s Lithuania’s “Greatest Generation” alongside tens of thousands of their peers who stayed behind and died fighting the Soviets as partisans. But I fully understand the impulse to consider them such. Even in their later years, after decades of work and struggle in the U.S., Lithuanian refugees in this collection—just like my retired factory worker father–are still thinking of how they can help their beloved native land and their relatives there.

Despite her personal losses and drastic uprooting as a young woman, Krutuliene muses, “It’s good that a part of us is here in immigration” because of the ability to financially support relatives back home–and from 1948-1991 to agitate for independence in ways impossible inside the U.S.S.R.

Petras Aleksa recalls, “My idea (after immigrating) wasn’t to have a job or money—it was important to make my own contribution to Lithuania.”

Damusis, a chemist on the verge of giving his homeland a cement industry at the time it lost independence, describes how advancing Lithuania through one’s highest educational and professional potential “was a rallying cry, and not just for me…Everyone (in the “DP” generation), no matter what they did, made something good of it (for Lithuania.) Twenty-two years of independence provided the impetus for this.”

Kavaliunas, the lifelong educator, concludes, “20 years of independence (1918-1940) imparted (so much) to Lithuanians, instilling in them the love of country—this was the huge capital that they brought with them from Lithuania.”

First published in Lithuanian in 2014, “We Thought We’d Be Back Soon” became available in English in 2017–just in time for the 2018 centennial of the restoration of a modern and independent Lithuanian state. There could hardly be a better time to hear the voices of the generation forged in the heady patriotism, passion for education, and service to country that independence inspired—so many lives inspired by one great idea.

Thanks to William Cellini, Jr., for retrieving the images for these posts from various websites.

Please write to sandybaksys@gmail.com if you live in the Springfield area and would like a copy of the book for $15 plus shipping. “We Thought We Would Be Back Soon” can also be purchased on Amazon.com