Lithuanian immigrant John Joseph Straukas, age 28, of Riverton, American Expeditionary Force, 1918. He received expedited U.S. citizenship as a result of his service to our country in World War I.

Editor’s note: An estimated 50,000 Lithuanian immigrants wore the U.S. uniform in World War I. William Cellini, Jr. writes today to commemorate all the immigrants who served and to explain how war could unlock the door to U.S. citizenship.

Immigrants in War, Citizens in Victory

By William Cellini, Jr.

Foreign-born citizens had served in the U.S. military for over 100 years prior to our country entering World War I. However, the “War to End All Wars” was unique in terms of the number of non-U.S. born men drafted into the military.

On April 6, 1917, Congress declared war on Germany and immediately passed the Selective Service Act requiring all men in the U.S. between the ages of 21 and 31 to register at their community draft boards. Within a few months of initial registration, about 10 million men across the country responded. By the summer of 1918, eligibility was expanded to include men 18 to 45 years old. Included in this wide net were native, naturalized, and alien men.

Kansteon Staikunas (Kanstantas Steikūnas), 28, born in Balninkai, Lithuania. Illinois National Guard (later the 33rd Division, U.S. Army) 129th Infantry, Company C. Killed in action during the battle of Meuse-Argonne, Oct. 11, 1918.

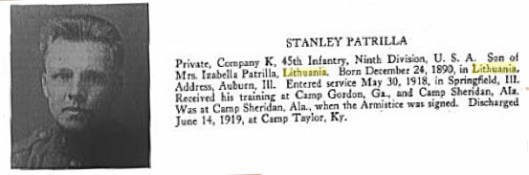

As the numbers of immigrant men called-up for military service increased, alien draftees were offered an expedited route to full U.S. citizenship regardless of their immigration status. Modifications for soldiers were made to all three key parts of the naturalization process: the Declaration of Intent, the Petition for Citizenship and the issuance of the Certificate.

Under the modified process, the residency requirement of five years before submitting a Declaration of Intent to become a U.S. citizen was eliminated. In addition, an expedited Petition for Citizenship was granted. Typically, the Petition required an oath of allegiance to be taken at the immigrant’s local courthouse. As an alternative, immigrant soldiers signed a pledge to the United States called a “written oath” and had two U.S. citizens verify their petition in writing, supplanting the need to go to a court. One can imagine written verification quite willingly being given by alien soldiers’ U.S.-born commanding officers and comrades-in-arms.

Finally, as an alternative to enduring the waiting period of several years to receive a Naturalization Certificate, once a soldier’s Petition was filed under the new war-time rules, the Certificate was granted immediately upon processing and approval. Conversely, immigrants asking for draft exemption or discharge from service would automatically have their citizenship process cancelled and would be forever disqualified from becoming citizens of the United States.

From May 8 to November 30, 1918, the government counted 155,246 immigrant soldiers among the newest citizens of the United States, not including an undetermined number of alien soldiers granted citizenship while stationed overseas.

Training and Commanding the Non-English Speaker

The unprecedented number of immigrants culled from a huge and diverse population of non-native English-speakers presented a challenge to their training and consolidation into an integrated fighting force. Seeing the need to address this, the U.S. War Department created a Foreign-Speaking Soldier Subsection (FSS) to assist in the training of immigrants who could not speak English.

Lt. Stanislaw A. Gutowski, a naturalized citizen born in Russian-occupied Poland, led the first step in the training process. Gutowski investigated FSS military camps of Slavic-speaking soldiers because he could speak Russian and Polish and witnessed the use of interpreters alongside commanders to instruct non-English speaking inductees.

This method proved ineffective, as inductees were often moved out of combat instruction and placed on kitchen duty. Consequently, Gutowski and his staff developed a plan allowing foreign-born officers to lead ethnic-specific companies, “without encouragement of immigrant ‘clannishness.’” These ethnic companies were formed as a contingency so that if called into combat, non-English-speaking soldiers would have an officer to communicate with them in the field.

Due in part to the numerous dialects spoken by inductees, the FSS favored using officers who spoke another language at home with family members over those who had learned a second language through study or travel. (This would have qualified the bilingual sons of immigrants.)

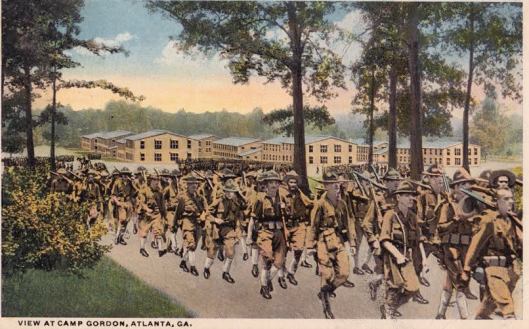

The influx of foreign-born inductees grew so numerous by the spring of 1918 that the U.S. Infantry created “development battalions” of non-English speaking soldiers. At Camp Gordon near Atlanta, an experiment was conducted in the training of several thousand non-English speaking draftees, who were divided into three groups: 1.) a Development Battalion of physically fit men; 2.) a Labor Battalion of disloyal and enemy aliens and 3.) a Non-combatant Service group of physically unfit men with a proficiency in a trade. At Camp Gordon, the two most populous ethnic companies were Polish-born and Italian-born soldiers. Training in the soldiers’ native tongues was supplemented by instruction in English grammar.

By the war’s end, one in five inductees in the U.S. military were foreign born.

Sources:

Abbott, G. (1921). The immigrant and the community. New York: Century.

Gentile, F. N. (2001). Americans all!: Foreign-born soldiers in World War I. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Infantry Association. (1919). Infantry Journal, Vol. 15. Washington D.C.: United States Infantry Association