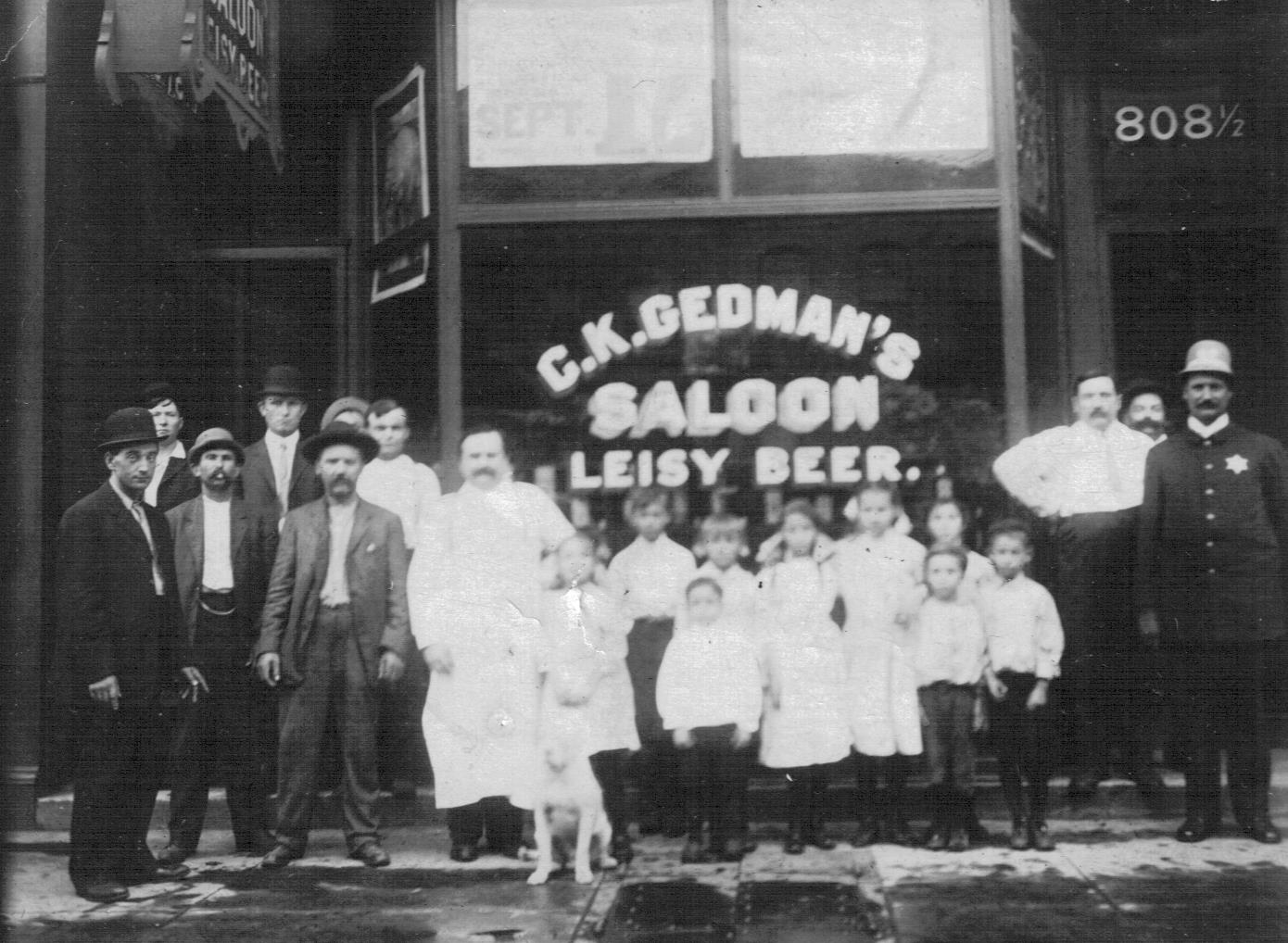

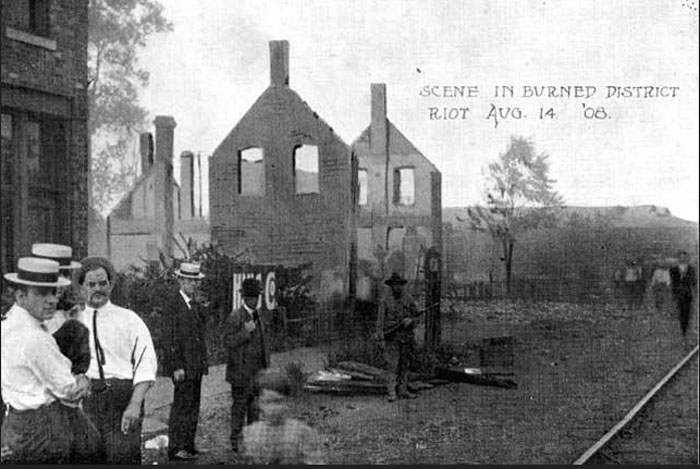

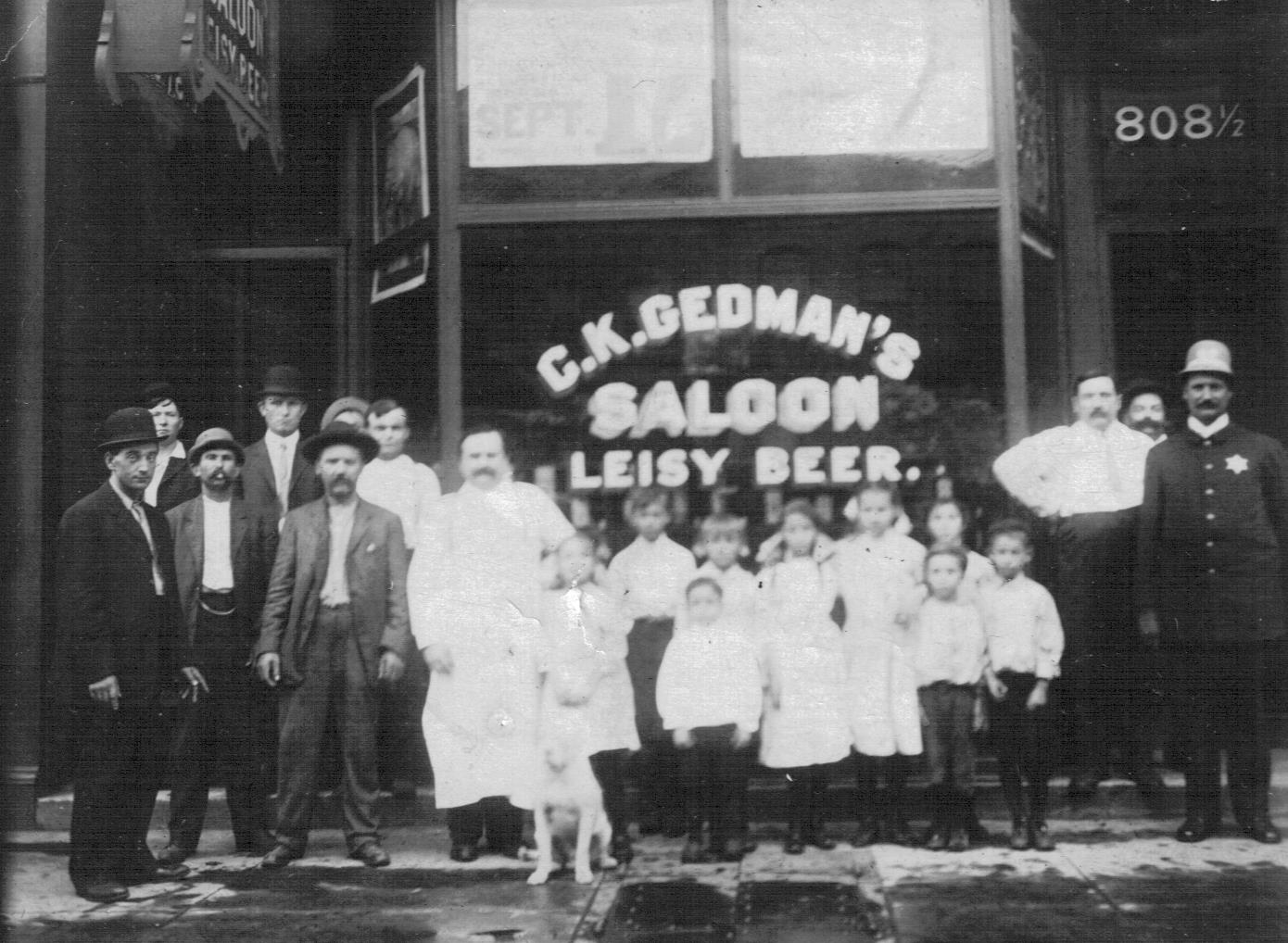

Charles Gedman Saloon, 808 E. Washington, 1908. Courtesy of Rita (Lukitis) Marley.

For two solid decades before the national Prohibition Act, Springfield was convulsed by its own local battle over booze. This wet-dry war pitted a largely native Protestant temperance movement against saloon owners and their patrons, who notably included thousands of newly arrived Catholic immigrant laborers from Southern and Eastern Europe.

Continuous wet-dry political battles from 1900 to 1917 threatened the very basis of the legal and regulated alcohol trade. Such extended insecurity about the direction of the law no doubt undermined its relevance in some minds. For this and other reasons, the clandestine illegal alcohol business so famous during national Prohibition actually began here decades earlier.

Even while alcohol remained legal, poor immigrants who saw opportunity in home brew, as well as those who couldn’t get a liquor license or live by its terms–conducted so-called “blind pigs,” selling illegally from the backrooms of stores and the attics of homes. Along with this pervasive small-scale disregard of alcohol regulation, Springfield’s extended wet-dry conflict also seems to have spawned significant political influence-peddling, as well as the beginnings of larger-scale bootlegging by violent criminals. At least one Lithuanian immigrant tavern owner, Joe Yucas, who cut his teeth defying municipal alcohol regulations, then local prohibition, moved on to defying federal Prohibition.

What follows is a history of alcohol politics in Springfield’s pre-Prohibition period.

From Saloons to Grocery Backrooms: The Ebb and Flow of Liquor in Early Twentieth Century Springfield

By William Cellini, Jr.

Citizens of Springfield, Ill., have long-preferred their city to be a liquor-friendly, “wet” town, as evidenced by their voting for and approval of alcohol sales and consumption laws. As a politically important city since the mid-1800s, Illinois politicians and Springfieldians alike contributed to the livelihood of the town’s entertainment venues, dining spots, and its profitable tavern business and vice quarter downtown.

But tavern life, and vice that at times accompanied it, also caused backlash from the community. Local temperance ordinances trace back to the 1840s, when a ‘lid’ law was passed in Springfield barring grocery stores from selling liquor on Sunday and prohibiting patrons from consuming inside the stores. This so-called “lid” also applied to the hours a tavern owner could serve patrons.1

That early Sunday ban was followed statewide restrictions on liquor in 1851.2 This so-called “Quart Law” prohibiting sales of alcohol in containers less than one quart and sales to minors younger than 18 was repealed only two years later in 1853.3 Thus, the die was cast for the back-and-forth battle that even reportedly involved Abraham Lincoln and fellow Springfield lawyer Benjamin S. Edwards in drafting the language of an anti-alcohol referendum in 1855 that failed to pass in all Illinois counties.4

The Anti-Saloon League

Around the turn of the century, local temperance advocates began to make in-roads through the Springfield chapter of the national Anti-Saloon League, founded in Ohio in 1898 by Protestant clergy and laypeople.5 The League’s aim was to eliminate taverns by electing prohibitionist candidates. In Illinois, it helped place a local option measure on a statewide ballot in 1901, whereby permits for taverns and liquor sales would be decided by the percentage of voters of any ward, township, city or county during a regular election. While the local option of 1901 did not pass, an option law did pass in 1907 following a campaign exposing crime, prostitution and the impact of alcoholism and vice on family life in Springfield.6,7

In the early twentieth century, alcohol-fueled violence ran rampant throughout Springfield, and taverns factored into the problem. After the statewide passage of the 1907 local option, a referendum on tavern regulation was offered to voters in the 1908 Sangamon County township elections. Springfield (Capital Township) voted to keep its taverns open and its liquor flowing. Two more local-option temperance campaigns failed in 1910 and 1914 (even with women voting in 1914), so that Springfield was not voted ‘dry’ until an April 1917 referendum.8

The Prelude to Citywide Prohibition: Springfield’s Booze Borders

Supply and demand of alcohol was at the heart of the wet vs. dry conflict. By 1904, the city had over 170 taverns throughout its neighborhoods and downtown. Twenty-five were on East Washington Street alone, in a section known as the Levee. This was the city’s vice quarter, lined with pawnshops, bordellos, flop houses, gambling dens and small eateries. Three taverns owned by Lithuanian immigrants by the name of Gedmins, Povilaitis and Rogalis were located in the 800 to 817 block of East Washington. East of that block was the predominately African-American section of the Levee.9

The Levee was only part of a larger tavern district spanning numerous blocks downtown.10 Taverns in the downtown district operated six days a week but closed on Sunday per the lid law. If a tavern served alcohol on Sunday, the operator could be fined or jailed by the city. In 1905, Alderman Gustave Timm, a barber of German descent, unsuccessfully introduced an ordinance to require any new taverns outside the downtown district to show proven support from the neighborhood in the form of residents’ signatures.11

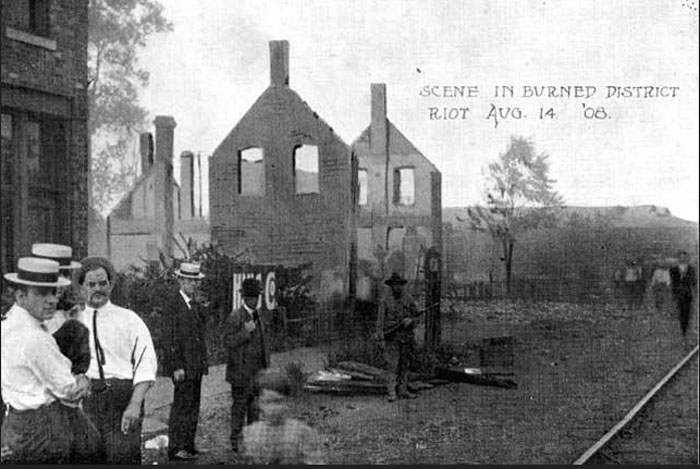

Aftermath of the 1908 Springfield (white) Race Riot. Courtesy of SangamonLink.org.

City Taverns and the 1908 Race Riot

In 1908, Springfield’s first local option referendum resulted in Capital Township casting 1,902 more pro-wet votes that pro-dry ones, defeating the so-called “Anti-Saloon” initiative.12 That August, alcohol played a role in the infamous white mob action known as the 1908 Springfield Race Riot. The trouble started when a crowd of white men and women congregated outside Springfield’s jail, calling for the hand-over of two African-American prisoners awaiting sentencing for the alleged murder of a white man and the alleged rape of a white woman. When the crowd learned the prisoners had been relocated out of town, they became enraged and destroyed a restaurant and the automobile of the white man who had aided in the prisoners’ transfer.

Then they went on a rampage, attacking and decimating the African-American section of the Levee while destroying nearby white-owned businesses in the process. “Barrels of liquor were thrown into the streets and bottled goods were carried away. The whiskey served as fuel…”13 After they finished with the Levee, the mob also unleashed its violence on a low-income, mixed-race neighborhood just east of the Levee known as “the bad lands,” setting ablaze African-American and white-owned homes.14

Immediately after the race riot, downtown taverns were closed under the order of the Chief of Police, who issued this warning: “Close that place down and do not open it again until you see the mayor.” Twenty-three taverns in various locations were found to have been in violation of the lid law and were ordered closed by the city because they had sold liquor immediately after the riots began. It was not until February 1909 that taverns in the city operated normally and the regular midnight lid was reinstated.15

Lithuanian Victims of the Race Riot

Following the unrest, deaths and injuries were reported in the Illinois State Journal, and at least one injured man listed was Lithuanian. His name was reported as “Alex Botwinis,” but likely his given name was Alex Povilaitis, the bartender and owner of 800 E. Washington St. when it was attacked by the mob.16

Julius Rogalis of 817 East Washington Street holds the distinction of being the only Lithuanian tavern owner in the Levee mentioned in detail by accounts of the riot published August 14-16. This is because Rogalis was arrested with two other men loitering inside his tavern in the aftermath of the riot on the morning of August 15th, presumably surveying the damage.

A tavern at 808 E. Washington was owned by Lithuanian immigrant Charles Gedmins or Gedman (see photo at the top of this post), but no mention of it is made in news coverage of the riot. As for the destruction of homes, although the bad lands were home to Lithuanian immigrant families, Lithuanian surnames are not included on the list of those whose homes were gutted by fire and looting during the riot.

The Votes Remain the Same

On April 5, 1910, another local option alcohol referendum was offered to citizens. Both sides predicted victory. Ernest Scrogin, Superintendent of the Illinois Anti-Saloon League, suggested only voter fraud could prevent a “dry” victory. Harold Webb, Secretary of the Manufactures’ and Merchants’ Association, predicted victory, but with hesitation.17 Webb’s uncertainty was washed away on a flood of pro-alcohol votes.

The post-election headline in the Illinois State Register declared, “Wets Win in Springfield By 1,432, and Capture Many Cities Throughout State.”18 Henry Davidson, Commissioner of Public Health and Safety, got a portion of his own version of a tavern ordinance handed to voters in a special election in 1911. Nearly 10,000 voters took to the polls and yet again, the prohibitionists lost. Even so-called ‘dry districts’ joined in the overwhelming rejection of more tavern regulations.19

The War on Vice and the 1914 Referendum

1914 was an election year and in advance of the vote, crime-fighting became a political issue. Mayor John Schnepp declared a war on “saloon cafés.” These cafés were rooms above taverns that women could patronize during serving hours, circumventing a city code that prohibited women from entering taverns.20 Gambling took some heat as well when Schnepp used his licensing authority against a myriad of gaming dens across town.21

Temperance advocates took advantage of the anti-vice political climate to place another anti-alcohol referendum on the ballot.22 To the prohibitionists, women voters were now an important demographic. “[Temperance support] centered upon the woman vote, which was a new factor projected into the wet and dry issue…” 23 According to SangamonLink, the digital repository of the Sangamon County Historical Society, “A carefully calibrated legislative strategy in Springfield (had) led to Illinois becoming, in 1913, the first state east of the Mississippi to grant women the right to vote.”24

Although women had ‘limited’ voting power, (Illinois’ ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution didn’t occur until 1919), the “dry” forces counted on their votes to swing the outcome of the referendum. After the votes were counted, the tally took aback local prohibitionists and tavern supporters alike: A majority of both female and male voters had cast their ballot to keep taverns open in both Springfield and Sangamon County.25

The 1917 Wet v. Dry Campaign

In 1917, prohibitionists and liquor interests battled it out in still another referendum. This time, each side looked to the female vote. Prohibitionists brought in Jason Hammond, an out-of-town strategist and pro-temperance organizer to craft their campaign messaging. Hammond assigned a captain and assistants to canvass each of Springfield’s 57 precincts, block by block, to assess temperance support. The Anti-Saloon League of Chicago also contributed resources to the local campaign.26

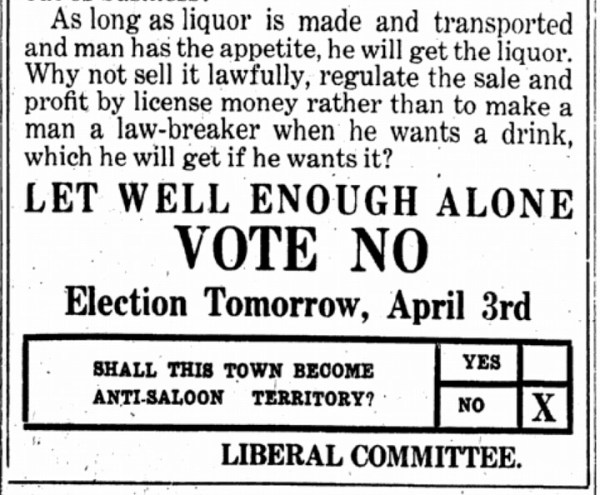

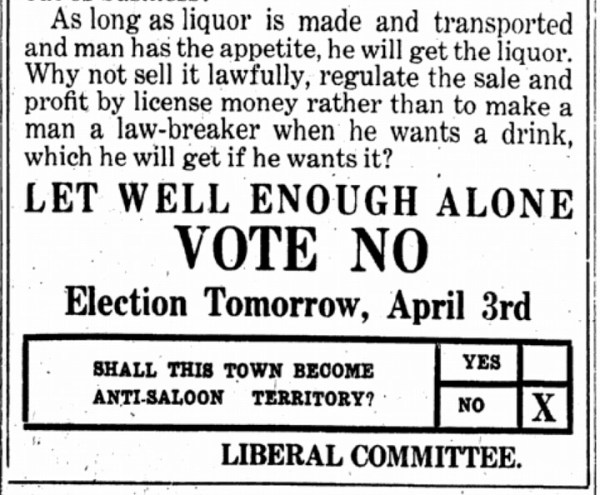

A public relations battle broke out in Springfield’s two leading newspapers between the Dry Committee and pro-tavern “Liberal Committee.” The dry message cited social ills like crowded jails, shattered family life and hard-earned money drunk away, largely sidestepping their traditional resort to Christian arguments. Meanwhile, the Liberal Committee argued that going dry would actually unleash higher levels of temptation, crime, and immorality, pleading with voters to “…regulate the sale (of alcohol) and profit by the license money rather than make a man a law-breaker when he wants a drink…”

For entrepreneurial immigrant and native tavern-owners relying on their saloon income to escape erratic, dangerous and low-paying factory and coal mining jobs, prohibition was the ultimate threat. “[The prohibitionists] propose to vote us out, take away our source of livelihood, and destroy both our property and business without recompense, which is not American fair play.”27, 28

The fact that city pensions were supported by tavern licensing fees also likely contributed to a reluctance to completely shut down Springfield’s taverns. In 1912, the Illinois State Register had reported, “the police pension [had] increased by $2,000, as it is the law that $10 of every [tavern] license shall be given to that fund. The firemen’s pension fund [also] increased by $500, as $250 of each license is given to that fund.”29 Springfield’s elected commissioners (in the city’s new system of commission government) wondered how to make up the shortfall in pension contributions should tavern licensing fees disappear after an anti-tavern vote.

That April, a reported 22,000 voters went to the polls in Springfield in spite of the fact that President Woodrow Wilson asked for a declaration of war against Germany the day before the election. This time, Springfield voted to put itself “squarely in the prohibition column,” the largest city in Illinois to do so at that time. The majority carried by only 469 votes, and as the temperance forces had long hoped, women made the difference, at last pushing the prohibition tally over the top.30

Vote totals were 10,764 for prohibition versus 10,295 against. Illinois law set midnight May 4th as the death knell for taverns in Springfield. 31

Leading up to the 1917 dry vote, some tavern owners and liquor interests anticipated that city-wide temperance would merely drive the alcohol trade underground. The website SangamonLink sums up what happened: “The 1916 city directory listed 208 saloons in Springfield; they all vanished in the 1918 directory, but were replaced by 80 “soft drink” parlors, a classification brand new to the directory that year. The Leland Hotel became a tea room, and some other taverns were, at least nominally, converted to pool halls, groceries, and other establishments where a knowledgeable patron could get an alcoholic drink with a knowing nod or password.”32

Prohibition Goes National

In many ways, Springfield looked ahead when it enacted citywide prohibition as early as 1917, owing to the fact that the U.S. temperance movement did not achieve ultimate victory until passage of the National Prohibition Act (a.k.a The Volstead Act) in January 1919. The Act took effect in January 1920 and prohibited the manufacture, sale and consumption of liquor nationwide.

Illinois State Journal, Dec. 3, 1933.

What followed was a period rife with bootlegging, gang wars, and countless police raids, arrests, and fines, mostly imposed on normal citizens for small-time alcohol-related infractions. Prohibition also led to tens of thousands of deaths from methyl or wood alcohol–as well as industrial alcohol that the government ordered poisoned in a tragically misguided program to discourage its theft and sale for spirit consumption by criminal gangs.

In the depths of the Great Depression, the National Prohibition Act was repealed by the federal government so that alcohol sales could be taxed to help pay for desperately needed public relief and jobs programs. National Prohibition finally ended in December 1933.33

Works Cited

1). Grocery Ordinance. Sangamo Journal, May 23, 1844. P. 3

2). City Ordinance. Illinois Daily Journal, Aug. 28,1852, P. 3

3). Grossman, J. R., Keating, et.al. (2004). The encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. accessed March 15, 2016, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1238.html

4). White, C. T. (1921). Lincoln and prohibition. New York: Abingdon Press. PP.141-143. accessed March 16, 2016, https://books.google.com/books

5). Grossman, J. R., Keating, et.al. (2004). The encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. accessed March 22, 2016, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1238.html

6). Talks Local Option Law. Illinois State Journal, Nov. 25, 1901, P.2

7). SangamonLink http://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=8193, accessed March 15, 2016.

8). Ibid.

9). City of Springfield Directory, R.L. Polk & Co., 1904.

10). Aldermen Go To Decatur: Saloon District Defined. Illinois State Register, Oct. 16, 1905, P.7

11). Mayor’s Veto Decides Scale Against Timm Ordinance. Illinois State Register, Oct. 31, 1905, P.5

12). SangamonLink http://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=8193, accessed March 20, 2016.

13). Levee District is Laid Waste. Illinois State Journal, Aug. 15, 1908, P.1

14). Senechal, R. R. (2008). In Lincoln’s Shadow: The 1908 Race Riot in Springfield, Illinois. Southern Illinois University Press. P.16

15). Midnight Lid “Pryed” Loose. Illinois State Register, Feb. 21, 1909, P. 1

16). City of Springfield Directory, R.L. Polk & Co., 1908.

17). To-Day Is Election Day. Illinois State Register, Apr. 5, 1910, P. 1

18). SangamonLink http://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=8193, accessed March 19, 2016.

19). Voters of City Decide Further Regulation of Saloons Not Necessary. Illinois State Journal, Dec. 15, 1911. P. 1

20). Pseudo Cafes Are Interdicted. Illinois State Register, Jan. 1, 1914, P. 11

21). Ibid.

22). Wet and Dry Fight Opens in this City. Illinois State Register, Jan. 2, 1914, P. 2

23). Sweeping Victory of Saloon Forces, Favored by Big Number of Women’s Vote, is Surprise. Illinois State Journal, April 8, 1914, P. 1

24). SangamonLink http://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=8193, accessed March 15, 2016.

25). Sweeping Victory of Saloon Forces, Favored by Big Number of Women’s Vote, is Surprise. Illinois State Journal, April 8, 1914, P. 1

26). ‘Drys’ Map Out Campaign Units. Illinois State Register, Feb. 7, 1917, P. 12

27). The Real Question For the Voters on April 3rd. Illinois State Register, Apr. 2, 1917, P. 10

28). Many Guesses As Fight For Dry City Ends. Illinois State Register, Apr. 1, 1917, P. 1

29). Will Have $50,000 in Treasury. Illinois State Register, Jun. 28, 1912, P. 5

30). Saloons Voted Out By Women; Majority 469. Illinois State Register, Apr. 4, 1917, P. 1

31). SangamonLink http://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=8193, accessed March 15, 2016.

32). Ibid.

33). Kyvig, D. E. (2000). Repealing national prohibition. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. PP. 178-179

Troy Mathews of the Chernis-Urbanckas clan shared his family’s long and happy association with the Illinois State Fair in the State Journal-Register newspaper on Aug. 19, 2016. I’ve pasted the text of that article below for those who missed it. I would have loved to have worked–exhibited or marched in a parade–at the Fair as a young person. (Looks like my family should have known the Urbanckases!) Mary (Chernis) Urbanckas is pictured above with her “Best in Show” hobby entry and ribbon, 2006.

Troy Mathews of the Chernis-Urbanckas clan shared his family’s long and happy association with the Illinois State Fair in the State Journal-Register newspaper on Aug. 19, 2016. I’ve pasted the text of that article below for those who missed it. I would have loved to have worked–exhibited or marched in a parade–at the Fair as a young person. (Looks like my family should have known the Urbanckases!) Mary (Chernis) Urbanckas is pictured above with her “Best in Show” hobby entry and ribbon, 2006.