This Wed. Lithuania Comes to Springfield!

27 Sunday Apr 2025

Posted in Sandy's Blog

27 Sunday Apr 2025

Posted in Sandy's Blog

13 Sunday Apr 2025

Posted in Sandy's Blog

Please come to the only free public performance in Springfield of the Suvartukas teenage folk dance ensemble from Plunge, Lithuania.

When: 5:30-6:30 p.m., Wednesday, April 30, 2025

Where: Lincoln Library, the Public Library of Springfield, Carnegie Room North. Free parking on the street and in the library’s underground parking garage.

Please come and bring your friends and family to welcome our talented, young performers from Lithuania! Enjoy the Suvartukas Ensemble’s energetic and artistic interpretation of classic Lithuanian folk dance subjects and themes.

This will likely be the troupe’s last visit to Springfield, so don’t miss out on the opportunity of a lifetime to enjoy an authentic Lithuanian cultural experience without ever leaving Springfield. For more information, email sandybaksys@gmail.com

09 Saturday Nov 2024

Posted in Sandy's Blog

By Sandy Baksys

In all our attention to vanished history, we can sometimes forget about the wonderful centenarians and near-centenarians among us who embody so much living history. I am thinking today of Lithuanian immigrant coal miner’s daughters Ruth (Petrokas) Lustig, 101, and Helen (Sitki) Rackauskas, 99.

The first local Lithuanian centenarian I heard about in passing while writing my book, “A Century of Lithuanians in Springfield,” was first-wave immigrant Petronella Marciulionis. Lacking contact with any living relatives, I unfortunately never got to write about Petronella and her daughters Anna, Mary, and Helen, who all sang in the St. Vincent de Paul church choir and lived in “Little Lithuania” area of Peoria Rd. and Sangamon Avenue. But I’ll bet Ruth and Helen probably knew Petronella and her daughters in Springfield’s thriving Lithuanian-American community of the 1930s and ’40s

Helen’s personal history has been covered in detail on my blog and in my book: specifically, in the 2016 edition of my book’s “Lady of Birds and Lost Little Ones” chapter, in which Helen details the immigrant story of her mother, Mary Ann (Yezdauski) Sitki. However, I never had the chance to write about Ruth. Then just last month, Ruth’s niece Trish (Chepulis) Wade wrote to me on the occasion of Ruth’s 101st birthday celebration to correct that omission.

Thanks for the heads-up and the photos, Trish, and a big hug and many congratulations from Springfield, dear Ruth!!

Ruth (Petrokas) Lustig and Trish’s mother Sylvia (Petrokas) Chepulis were sisters: the only children of Lithuanian immigrants Stanley W. and Katherine (Rieskevicius) Petrokas of Springfield. That makes Ruth the aunt not just of Trish, but of Sylvia and Joe Chepulis’s other children: Mary, John, and Joe Chepulis (recently deceased) and Bernadine (Chepulis) Dombrowski (also deceased).

Ruth currently lives with two of her daughters in Lakeville, Minn. But she was born in Springfield and graduated Lanphier High School, followed by the St. John’s School of Nursing. Because World War II was still on at the time, Ruth was recruited right out of St. John’s to serve for one year in the U.S. Army Nurses Corps.

Shortly after returning from her WWII service, Ruth moved to Elgin and spent 40 years in mental health nursing in Chicago’s western suburbs until she retired and moved to live with her daughters in Lakeville.

Ruth is also the mother of six children.

(These last two photos are of Ruth in the U.S. Army Nurses Corps and graduating from St. John’s Nursing School.)

08 Tuesday Oct 2024

Posted in Sandy's Blog

Read the story of Alda Raulinaitis, the daughter of a Lithuanian immigrant coal miner in Springfield who, despite her humble beginnings, appears to have been something of a polymath, a true Renaissance woman, in addition to a fine artist. It would be wonderful to find out anything more about her, for example, if she had siblings, husband or children, or an association with St. Vincent de Paul (Lithuanian) Catholic Church before she left Springfield. It is likely that her first name was originally Aldona, just as her abbreviated last name, Raulin, was originally Raulinaitis.

A big thanks to Mike Kienzler of SangamonLink for uncovering her story, complete with photo. https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/springfield-high-school-sketches-1930-alda-raulin

08 Wednesday Feb 2023

Posted in Sandy's Blog

Dear readers, we are researching some of the first Lithuanian families in Springfield for a future blog post and seek information from the descendants of the following late-19th Century immigrants. Please email sandybaksys@gmail.com if you can help with info or photos. Thank you!

Viliumas [William] Kasper and wife, Martha Tonila [Tunila]. He came to the U.S. in 1888. They had Kate (born 1887) and William, Jr. (born 1898).

Motiejus [Matthew] Patkus (Petkus). He emigrated in 1889 and seems to have married a non-Lithuanian (Agnes Reid). Their kids were Ralph (died 2009), George (died 1982), Matt (died 2007), and Mary (died 1983).

Ignatius [Enos] Kasper emigrated in 1890. He married Marcella Tonila (maybe brothers marrying sisters?)

Thank you for any help you can give!

22 Monday Aug 2022

Posted in Sandy's Blog

At 6:30 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 15, 2022, the Illinois State Museum in downtown Springfield will show the 1-hour documentary film, “Displaced.” This FREE public showing is co-sponsored by the Lithuanian-American Club of Central Illinois in memory and honor of our own “displaced persons” (“DPs”), still living or deceased, who found refuge in the U.S. after World War II. (See the movie trailer at this link: https://vimeo.com/297785221 )

Please come to the Museum’s downstairs auditorium and bring a friend. The film will be publicly dedicated to the following individuals and families: Irene Blazis, Romualda (Sidlauskas) Capranica, Vince Baksys; Kaz and Vida Totoraitis; Alphonse, Lucyna, and Grazina Maculevicius; Constantine, Helgi, and Mike Lelys; Vita and Ben Zemaitis; Paul, Sophie, and Hank Endzelis; Stephanie, Walter, and Violeta Abramikas; and the Uzgiris, Sidlauskas, and Paulionis families.

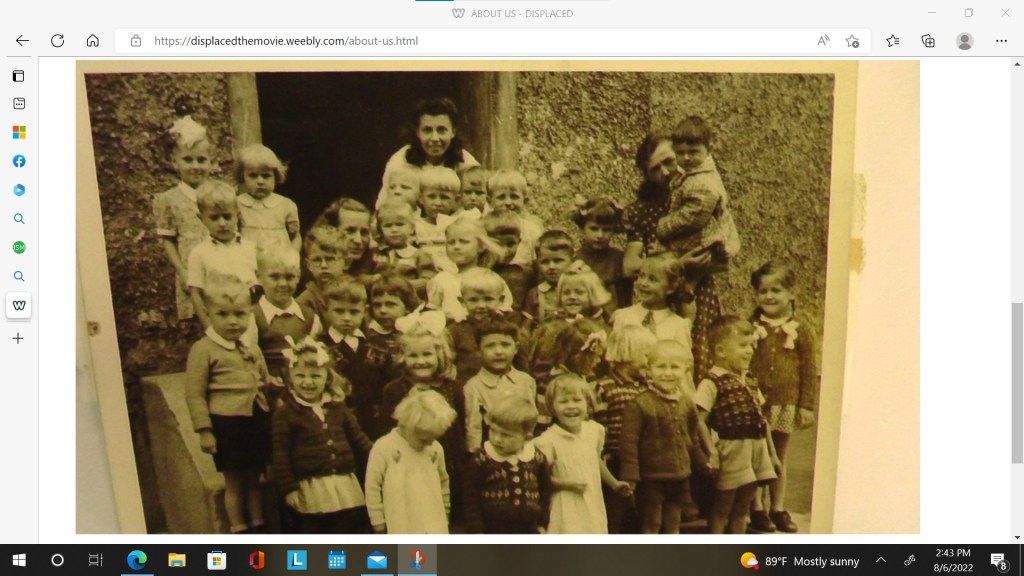

“Displaced” is the story of the refugees who fled westward into Germany from Lithuania and other Eastern European countries in the final, desperate days of WWII to escape the Soviet conquest of their homelands. The story is told by former child refugees, whose interviews are illustrated with newsreel footage and animation.

Learn how the refugees believed they were leaving only until the end of the war, when they expected the Soviet Army to retreat and the independence of their homelands to be restored. See how refugees were accommodated if they were lucky enough to reach the American, British, and French occupation zones of post-war Germany, and often coerced to return to Soviet-occupied homelands, where they feared for their lives.

See life in the refugee camps established by the precursor to the United Nations. Learn how the refugees became immigrants when the U.S.S.R. did not withdraw from their homelands and they had to re-start their young lives in exile, their parents often working as manual laborers in countries with post-war manpower shortages.

Several hundred World War II displaced persons (“DPs”) from all over Eastern Europe arrived to work in the Springfield area, thanks to relatives, churches, and employers who sponsored them under the U.S. Displaced Persons Act of 1948. Please join us at the Museum Sept. 15 to commemorate this history, and reflect on the massive, new Ukrainian refugee crisis in Europe.

Questions? sandybaksys@gmail.com

19 Saturday Mar 2022

Posted in Sandy's Blog

On March 12, 2022, I delivered updated insights about “Lithuanians in Springfield” in a Zoom presentation sponsored by the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture, Chicago.

Below is a transcript of that Zoom presentation, edited for brevity and clarity in some cases, and conceptually enhanced in others. Many thanks to Draugas News for providing the original transcript for my editing. You can also watch the presentation for free at this link: https://vimeo.com/687830727

Sigita Balzekas: This is the book club presentation of the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture. Located in Chicago, we are the largest repository of everything Lithuanian this side of the Atlantic, and we’re just exceedingly proud to have Sandy Baksys with us here today. Sandy, as she will tell you, I’m sure, is a daughter of a Lithuanian immigrant, a displaced person (“DP”): her father who immigrated after World War II, as am I. My parents immigrated to Canada.

Sandy’s story is set in Springfield. However, it is truly a universal story of how immigrants informed by the experiences that they’ve had before they immigrate to a new country, what they bring with them, how some of those unfortunately tragic events sometimes affect them in their present lives and potentially affect their ability to assimilate what they cherish. All these things are revealed in Sandy’s incredible book, “A Century of Lithuanians in Springfield, Illinois.”

Now, Sandy is a Springfield native. She was a newspaper reporter. She holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University. She also holds a bachelor’s in Italian and a master’s in English literature from the University of Kentucky. If you read her book and see how beautifully it’s written, no doubt she’s an English major. She has a lovely gift for expression.

From ’89 to ’91, Sandy was involved with what they call the “Singing Revolution,” Lithuania’s reestablishment of independence, through the Lithuanian Communications Center in Philadelphia.

In 2012, she spearheaded the erection of a historical marker in Springfield, Illinois, and launched a blog at http://www.lithspringfield.com .

Sandy Baksys: Hello, everyone. Thanks, Sigita. And welcome everyone. Thank you for being here today. Thanks to the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture for supporting my book. It’s hard right now to think of anything but the war in Ukraine and how much the faces of the traumatized refugees make us think of our own Lithuanian parents and grandparents, who fled their homeland at the end of World War II.

The causal relationship between war and the exodus of those 60,000 Lithuanians to escape the advancing Soviet army is obvious. But only about 50 to 100 World War II displaced persons, so-called second wave Lithuanian immigrants, ended up in Springfield, the hometown of President Abraham Lincoln.

A much larger number, 2,000 Lithuanian immigrants, arrived here during the first wave of immigration between 1870 and 1914, when up to 500,000 left a country of an estimated 2.5 million. But I would like to propose that even though this first wave departed during what was apparently peacetime, they were also, in a very real sense, refugees of a prolonged and no less brutal, form of warfare.

Most of us know about the Russian czarist oppression of political, religious, language, and human rights in Lithuania from 1795 to 1918, after which the empire fell apart and Lithuania gained its independence. One goal of the Russian conquest and the annexation of Lithuania in 1795, and onward, was to dominate and degrade Lithuanian existence so completely that the people would remain stripped of their rightful majority power in their own homeland. In the service of this goal, there was a crucial alignment of the Polish-Russian feudal nobility with the Russian czarist empire that made feudalism a powerful weapon of war against an entire nation.

Under feudalism, which had older roots in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, most Lithuanians were enslaved to the owners of large agricultural estates: bonded to the land, which meant that, whoever owned the land, owned them. Serfs could be whipped, killed, imprisoned, and separated from their family with impunity. Czarist forces would help capture and return escaped serfs. Sounds a lot like slavery, right?

Although the czar declared an end to feudalism in 1860, just like when African-American slaves were freed in 1863, nobody got any land, no “40 acres and a mule.” So, for the next 65 years, freed serfs and their descendants in Lithuania were only free to remain destitute sharecroppers or hired hands on the same kind of large estates where they had always worked.

To break out of that bleak stasis, it was necessary to take advantage of the only new right that came with the end of feudal land bondage, the new freedom of movement. Hundreds of thousands of Lithuanian peasants migrated first to industrialized Scotland and England, then to U.S. factory and mining jobs. Once here, they participated for the first time in a cash instead of a barter economy. The majority were illiterate. And I have to say, based on my research, many were heavy-drinking–maybe big-hearted–but heavy drinking, volatile, and just on the edge of violence. Yet to be fair, that would have been the ideal “help wanted” description for the kind of dangerous coal mining and factory jobs that “roughneck” Lithuanians and other European immigrants of the time were expected to fill.

The U.S. coal belt extended west from Pennsylvania, where Lithuanians first landed, across to West Virginia, southern Illinois, and even counties north of Springfield and east to the Westville area near Danville–and throughout southern Illinois. And everywhere, it was extremely dangerous work.

According to my research, about 10% of Lithuanian miners in this area were killed over the length of a career that spanned perhaps 20 years. Another 15-20 percent were injured or maimed. And almost every miner besides that had lack lung disease. And those men typically died between the ages of 40 to 60 while struggling for breath all night long. (All lung problems are worse at night because the lungs are compressed when we lie down.)

In my book, there is a male immigrant who understandably gets drunk and sings Lithuanian songs every evening before struggling all night to breathe, constantly waking to expectorate into a bucket. In another chapter, we learn that mining’s toll on men’s health produced something called “the bank of grandma,” when long-lived women, as grandmothers, became matriarchs and repositories of their immigrant families’ savings.

My own grandfather had been a coal miner in Pennsylvania before he returned to Lithuania to buy land around 1910. My father told me that his father died at age 47 of pneumonia, but because Dad was six or seven at the time, I don’t think he ever made the connection with black lung. Yet one day, while writing my book, that connection leapt to mind, and I’ve felt sure ever since that my Lithuanian grandfather’s pneumonia became fatal because of underlying miner’s lung disease.

In the early 1900s in Springfield, there were probably three times as many single as married miners. These single men boarded with married miners and their families not just in Springfield, which allowed them to move from house to house, but throughout the coal belt, which, included links between Springfield and Coalton, Oklahoma, and of course, with the rest of Illinois.

Many of these single miners laid their bones in desolate, often lost, Lithuanian cemeteries across the U.S. coal belt, such as the abandoned cemetery at Ledford, Ill., which has been a project of youth from the Lithuanian American Community to restore and repair. In those same lost Lithuanian cemeteries are many perished babies and children, who also had no descendants because they never even got to grow up.

All over the U.S., first-wavers insisted on being buried in their own cemeteries. This resulted in Lithuanian cemetery neglect and even vandalism in smaller communities, like those in southern Illinois, when miners had to move away due to an over-supply of labor, union-busting, or the exhaustion of local coal seams.

In larger places like Springfield, Illinois’ state capital, a larger and more diversified economy made it possible for a stable, first-wave community to take hold and endure for almost 100 years. Such communities were able to build all the original institutions of Lithuanian America, churches and social clubs that lasted long enough at least to welcome their share of the second wave and help those new immigrants keep their language and culture alive until Lithuania could be free and independent again.

Sigita Balzekas: Everyone, as you said, is preoccupied by the events in Europe at this time and witnessing the mass migration from Ukraine, which reminds us of what was happening at the end of World War II when our parents fled.

But, Sandy, there is one thing that I wanted to highlight briefly, and that is, what was specific to Springfield, besides coal mining, that drew so many first- wave Lithuanian immigrants? What made them move there from Pennsylvania?

Sandy Baksys: This is something that’s not in my book because I learned it from continuing reading and research. But wages for coal mining were somewhat higher in Illinois than they were in Pennsylvania because mines unionized earlier here. So, one of the reasons that miners moved on, besides an oversupply of labor in Pennsylvania, was higher wages per ton of coal. Also, I would say land.

We have very fertile land here, and almost all of it is flat and not constricted by the narrow hollows of the mining areas in eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. Nor was farmable land here made scarcer by massive, surface strip-mines and wildcat mining, the so-called “coal holes” dug into the hillsides of Pennsylvania. And the availability of extremely fertile instead of rocky land was important because the first-wave immigrant families were mostly growing their own food, just as they had in feudal and post-feudal 19th century Lithuania.

The feudal lord didn’t feed his serfs any more than the master in the big house provided American slaves’ meals. So, in addition to their forced labor on the large feudal estates, Lithuanian serfs had been permitted a small parcel to grow their own food. And after they were freed, continuing access to even that small parcel for bare subsistence was probably contingent on ex-serfs continuing to perform serf-like labor on the estate.

Fast-forwarding to immigration, these subsistence farming skills were extremely useful—they could have even made the difference between life and death. And being able to get more and better land around Springfield increased an immigrant’s chances still further. Every family had a huge garden, but some even had truck farms. They acquired a little rural land just outside town and could raise surplus vegetables beyond what the wife canned for the winter, which could be sold.

Sigita Balzekas: Now, you had also mentioned in the book that some of the coal mines would close, that the veins would be exhausted, so there was not a secure job in mining. In effect, by the time a lot of the immigrants arrived in the Springfield area, they discovered that mining opportunities were already drying up. So, what other kinds of jobs did they find in Springfield if they couldn’t mine?

Sandy Baksys: Very good question. But, let me talk about the whole mining household. You had the woman growing food because you couldn’t even go to a supermarket back then. There were just little, family-owned, corner stores where you could get things like flour and milk that weren’t the woman’s job to produce from her garden. The immigrant household would also buy a pig from a nearby farm, slaughter it (every family had a trained butcher), then use the whole pig for dishes like pig’s feet, blood sausage, aspic, head cheese, you name it.

Additionally, there was a symbiotic relationship between the immigrant household and the three or four single miners who boarded with them at any given time. In exchange for the woman of the house feeding them and doing their laundry, these single males provided extra cash for the family. This often compensated for the wages lost when the husband/father drank away his pay before he even got home. I think the miners got paid on Saturday and many of them immediately cashed their checks and went from tavern to tavern, living it up. So, the extra income that the household could earn from the boarders was very important to keep it going, especially if it was paid to or held by the wife/mother of the family.

As to the closure of mines, every summer they closed because there wasn’t a need for coal and whatever buyers needed, they would stockpile through April. The mines here were closed every year, seasonally, from May to September. So, every summer, idled men would cut cemetery grass with scythes. They would dig basements and graves. Some worked their own truck farms and others probably hired out to neighboring farms.

And then there was the problem you mentioned, that by the time the Lithuanian miners arrived in Springfield around 1900, there were already too many miners for the number of working shifts available each day or week. And even in that six-month working season—when many of the mines wouldn’t even be open every day–there was job-sharing to try and make sure every mining family got some hours. Men who were either having a bad day with black lung, or who wanted to increase their chances of getting working hours, they would bring their young sons into mining work. You can see how having more members of the family able and certified to work, even boys as young as 14, would be like having more tickets in the job-sharing lottery.

But finally, the coal from the mines here was overpriced due to higher union wages and less mechanization. And many of the mines had a lot of labor conflict from the owners trying to mechanize and reduce wages. The owners did that especially during the Great Depression, the worst possible time for local miners to take a reduction in jobs and wages. This led to the central Illinois Mine Wars 1932-36 between the UMW and an upstart union that rejected a contract that cut miners’ wages by 25%, that John Lewis and the UMW wanted to press upon them.

So, basically, there was a short heyday for mining here that the Lithuanian immigrants got into, and that was probably just from the very late 1890s through the 1910s, with labor trouble and job losses intensifying in the 1920s. As a result, a lot of Lithuanians who originally built the local Lithuanian church, St. Vincent de Paul’s, moved on to jobs in Detroit and Chicago.

Sigita Balzekas: It didn’t occur to me that it was seasonal, that they weren’t just stockpiling through the summer months to have more of it in the winter months. It never occurred to me that coal mines offered seasonal labor. Were these strip mines primarily, or were they underground or both?

Sandy Baksys: In Illinois, it was “soft” sulphurous coal, deep-shaft mining—something like 200 feet down to the bottom of the shaft. I don’t know all the terminology, but shot firers used gun powder to blow down walls of coal. There were timber men who put up the timbers in the passageways. If they didn’t do a good job, you had a slate fall, which was a roof fall. People got killed all the time in all kinds of ways.

In the 1990s, I remember going to the funeral of a miner who’d been paralyzed in the 1960s. He was a second-wave Lithuanian immigrant by the name of Tadas Rizutis. But even in some photos in my book, there’ll be a guy that the caption says, “lost his arm in a mine” or “his brother was killed in a mine.” I have a whole section on 33 Lithuanian mine deaths that occurred, basically, from 1900 to about 1945, just from accidents resulting in multiple deaths. We don’t even have any record of single-death accidents or accidents in which people were maimed but not killed. And, there was a lot of maiming.

For this reason, marriage was not a very stable institution for the first -wave immigrants. There were so many deaths and dismemberments, disablements, black lung, early death. Marriage was a whole different thing than I expected to find in a Catholic community. There were sequential marriages, divorces, adoptions of your new spouse’s kids from another marriage. I mean, just a lot of what I call blended families.

Sigita Balzekas: How did the community support these families? What social services did they provide?

Sandy Baksys: Many of the immigrants organized around their church. There were what we call fraternal benefits societies, mutual aid societies, where you’d pay a certain amount per month and get a little booklet for what was essentially death insurance. If you got killed in the mines, then your survivors would get a certain amount to bury you. There might have also been disability benefits from these societies, I don’t know. (Recently, I read that freed slaves in the United States also buried their community members the same way way.)

Some of the first nodes of economic progress were the many Lithuanian-owned taverns because, guess what, that was a very ripe business model for hard-drinking Lithuanian miners. In my book, there is a tavern owner who is said to have bought life insurance policies to be able to bury his destitute customers. There was a sharing of canned food and other garden products in the neighborhood–I think there was much more of a communal life at the neighborhood level than we have today.

Sigita Balzekas: Now, you talked about these transient men. How did they live? How did they integrate in the community? Where did they live?

Sandy Baksys: Sure, they were the boarders I mentioned earlier, like room and board. Many first-wave families in my book would take up to four single male miner boarders to supplement the family’s income. One of my informants said her immigrant mother-in-law used to wash their backs in a galvanized steel tub to get the black coal dust off after they came home from the mine.

I think that they were the source of a lot of carousing in Springfield, to be honest. They carried from the old country a certain social and spiritual degradation, illiteracy, lack of education. They’d come from a very violent place. This was underscored when I went back and read the chapter in my book about letters that elderly parents would send to their first-wave sons in the United States, asking them to come back and visit (after Lithuania became independent) so the parents could see them one more time before they died.

And in one of these letters, it says, “Son, don’t be afraid. Nobody abuses the poor people anymore. Nobody beats us, takes us for unpaid labor, imprisons us without reason. We have rights now.” And that really tells you about not just the change brought by the new Lithuania for Lithuanians, the independent country that was founded in 1918, but also about the violence by the ex-feudal nobility and their cronies who for 65 years after the end of feudalism were just as powerful as during feudalism–and had all the land.

So, many of the transient, rough-neck single miners were not the type of people that you’d necessarily want to marry or meet in a dark alley. But according to one of my informants, long-term, aging boarders who never married became members of the family they boarded with, treating the children of the household as their own children. And, I’m sure the feeling was mutual.

But let me get into alcohol for a minute. Alcoholism was one of the terrible diseases and industries of the first-wave immigrants. Alcohol was a way of life and still another, probably necessary, way of earning income. Many Lithuanians and other Catholic immigrant nationalities filled the gap created by local “lid laws” that made getting your alcohol illegal on Sundays or after midnight the rest of the week, when saloons were ordered closed.

So, Lithuanians, Irish, and Italians would make and sell unlicensed alcohol in so-called “blind pigs,” or in the back rooms of corner groceries or in taverns that remained open illegally. Alcohol in Springfield wasn’t entirely prohibited until 1918 or 1919, but there were legal restrictions by township on where and when and by whom it could be sold. Bootleggers satisfied a thirst for alcohol that knew no such legal boundaries. They started making and selling it in the neighborhood.

And then once federal Prohibition hit, bootlegging became a bigger game and was consolidated by criminal gangs because of the higher volumes and risks involved. But the single male miners, the boarders, they would often help the lady of the house with a still to put or keep her in the alcohol business after her husband had been killed or disabled in the mines. Some Lithuanians had their kids deliver in the neighborhood, had the wife push infant “hooch” down the street under a blanket in a baby carriage.

I didn’t put this in my book, but I really believe that some of the larger taverns probably had brothels attached because of all these single men with no wives. I can’t explain all the reasons why they didn’t have wives, but one was that there were many more Lithuanian men than women who immigrated, and I never came across even one case of a Lithuanian, first-wave male marrying a non-Lithuanian female.

Sigita Balzekas: Another question I had was, did the taverns also have boarders living in their buildings?

Sandy Baksys: One of my informants, Jerry Stasukinas, his dad Albinas ran Alby’s tavern for many years. And he said that there were so-called “guests of the taverns.” These would be the very destitute, hopeless alcoholics that would be taken care of, allowed to dry out at times, but I think, at other times, also still given alcohol. It’s hard for me to say exactly how it worked. But the taverns would have the tavern-owning family living behind or above. And then they also had separate, adjacent buildings and rooms. And sometimes, dependent alcoholics would live there.

Jerry said that he’d find alcoholics sleeping on his dad’s couch at the back of the tavern. Others would join the family for meals. “He would try to give them a job and make them a man again,” Jerry told me of his dad. At one point, thanks to a city directory search by one of my research volunteers, Bill Cellini, Jr., I found my own, lost immigrant great aunt had been the “guest” of the Railroad Tavern and was living in a little adjacent building that had its own street address.

Along the same lines, I also found out in my research that my dad had two American-born first cousins– one son, each, of his two immigrant aunts–who had criminal records. But getting back to the victimless crime of illegal alcohol–when Prohibition ended and alcohol was legal again, I think the loss of the income from illegal production and sale was significant for many immigrant families.

And it couldn’t come at a worse time, coinciding with the major economic disaster of the Great Depression in the early 1930, as well as the Central Illinois Mine Wars, when more than half of the miners who still had jobs went on an extended strike. It was a time of great crisis, and the combined effects seemed to produce a lot of property crime, especially among young boys who were trying to help their families. Two very young boys in my book were shot to death while stealing.

How many people after Lithuania declared its independence on Feb. 16, 1918, returned to Lithuania? And what were the circumstances of that return? Everyone always assumed that in the United States, the streets were paved with gold. They would have all this money, they could help the family back in Lithuania. What was the reality?

Sandy Baksys: I tried to investigate returns. One of the researchers for my book, Bill, Cellini, Jr., wrote a chapter about, like I mentioned before, these letters from home, from the old who were left behind in Lithuania. Coming to America was coming to work. If you looked at the congregation at St. Vincent de Paul Lithuania Catholic church on a Sunday in 1915, when it had 1200 worshippers, you would have seen a sea of young people. A lot of old who had been left behind did receive remittances from their mining and factory-working adult children in the United States, but they also wanted to see them again before they died.

I really don’t have a count even on how many immigrants went back to visit, but we did discover that even that was prohibitively costly because, first of all, you only got half-a-year of work in the mines in a best-case scenario, and you had to do other manual work in the summer. The cost of too much time away from work was prohibitive. I think that some people did go back like my grandfather, (although he went back around 1910, before independence), because they’d always just intended to come over here, earn money, and then go buy land and live as Lithuanians in their own country.

I think that one factor that encouraged it was that Lithuania did not suffer the same Great Depression as in the United States after 1929. And throughout the 1920s in Lithuania, the situation was steadily improving. There finally had been significant land reform in 1924 that finally gave viable farmsteads to more than 140,000 peasant families. Elders were writing to their immigrant sons saying if you come back now, you have rights; those who were once high and mighty are cut down to size. Because of letters like that, and the improved situation, I think that some did go back.

Sigita Balzekas: Now, what’s the community like presently? How many Lithuanians live in the Springfield area? Do you still have a tight-knit group?

Sandy Baksys: One of the reasons why I spearheaded the historical marker and started the blog in 2012 was that there were only, I don’t know, six or seven children of the first wave left, and they were quite elderly. I managed to get some of their stories. The second wave was never numerous here: 50 to 100 people who didn’t all stay. They went to be in communities like Chicago with more jobs, where they could also live a more Lithuanian life. And then when the diocese closed the Lithuanian Catholic church and demolished it by the mid-seventies, that was a huge blow.

I would also say that there was so much assimilation. If you count from 1900 to 2000, how many generations is that of first-wave descendants intermarrying with non-Lithuanians? So, what really happened was, after three or four generations, you’re down to 1/8, 1/16 Lithuanian, and many young people didn’t find that meaningful, which really diminished people who identified with a once-vibrant community.

Lastly, Springfield does not get many fresh Lithuanian immigrants. We must acknowledge that mass out-migration is bad news for Lithuania because it results from foreign invasion or oppression–or their after-effects–driving people out as soon as they can leave. It’s also a catastrophe for the growth and progress of the country. But even from the great Lithuanian exodus after 1991, we didn’t get many immigrants in Springfield because jobs have been declining with the state of Illinois for years. To make matters worse, in just the last three or four years, we probably lost 10 elderly founding members and officers of our local Lithuanian-American Club, of the 30 or so long-timers who remained: people who are irreplaceable because they won’t be replaced.

And this brings to mind something we haven’t touched on yet: the support of the first wave for the “DP” second wave. The first wave didn’t do as well financially as you might have expected in 50-plus years in America because of two world wars and the Great Depression. But families here did sponsor a total of 50 to a hundred DPs, often their own distant relatives. The saloon owner Sam Lapinski, who was also a trustee of the Lithuanian church, housed the Abramikas family in an apartment above his tavern. There was a lady, Julia Wisnosky, who was very involved with the founding of the Lithuanian club, who adopted a war orphan from Lithuania.

Sigita Balzekas: That’s an excellent point, Sandy, because I don’t know if people are aware that, in order to immigrate (under the U.S. Displaced Persons Act of 1948), you had to be sponsored by someone here in the U.S.

Sandy Baksys: I learned that my “DP” father had to have a housing sponsor, his paternal aunt Mary Yamont, and she had to find an employer who would certify in writing that he had a job for Dad. Then, when my father first arrived in the summer heat of June 1949, he lived with his aunt and her three adult children in a one-bedroom house. Two of them slept in the living room, two in the bedroom, and one in the kitchen.

Sigita Balzekas: I did want to mention the issue of frugality being very much a characteristic of immigrants who’ve experienced challenges in their previous lives before coming to the United States, and then remaining exceedingly conservative here and fearful that one day all of this, too, will be lost. You talk in the book about the effect that that had on you, growing up, with your “DP” father being as careful and cautious as he was–yet your American-born mother trying to find ways to make opportunities for all of you to enjoy your life in the United States.

I totally identify and I remember you used a phrase, “the discipline of self-deprivation,” which I think is just right on. I also remember my parents always saying that whatever surplus there was, it went to Lithuania or in support of Lithuanian causes.

Sandy, you and I grew up at about the same time, so we saw the same things on TV. (Well, we didn’t even have a television until the mid or late sixties.) But we both saw these happy consumerist homes, the latest comforts. People underestimate the stress an immigrant child feels about fitting in. What was it like for you growing up in that kind of home?

Sandy Baksys: First, you’re not exactly living an independent life. You’re an adjunct or an attachment of your immigrant parent. And the more dysfunctional the parent is, the more upset or the more PTSD he or she has from being a refugee and from the war, that becomes an unrelenting darkness that’s at the center of your life.

That darkness becomes very big and when you’re a child, it kind of fills the house and presses you up against the wall so there’s not enough room for you to develop much of an ego or personality. You are always compensating for your parent’s strangeness, their invisible trauma from their previous lives that you know nothing about. I also grew up a girl in the very materialistic, faddish 1960s, where there were even different toy fads every year and skirt lengths that went from mini to maxi to midi in, like, just three years. Our family couldn’t keep up—didn’t even try—so I think my sisters and I had a kind of hopelessness about ever fitting in.

And what I learned, writing my book, is that family dysfunction or strife on a large scale can impact demographics. There’s one point in my book where I talk about “the enduring immigrant family of origin,” and another point where I list all the factors that, initially surprisingly to me, limited reproduction by the first wave. My dad had six American-born cousins from his first-wave paternal aunts, yet only one of those six cousins had just one child. I am one of six daughters of a second wave parent, and none of us has any children. Personally, I would say my main family affiliation is still the family I was born into, my family of origin. And I think that has a lot to do with my immigrant family experience.

In the first wave, many American-born adult children didn’t move out of their mother’s home until they were in their late 30s, 40s, or ever. Economic barriers to independence combined with the weak or missing personal boundaries between immigrant parents and their children that I just discussed to keep adult children at home. For example, during and after the Great Depression, all members of the immigrant family had to pull together just to survive, often in a small family business like a tavern or a corner grocery. Adult children just kept living and working with their immigrant parents and never married–or if they married, married late, like two of my father’s six cousins who never had children.

Sigita Balzekas: Is there anything you’d like to talk about that we haven’t touched on yet?

Let me mention some of the individuals in my book. You’ll find an immigrant mother who lost five of her seven children in childhood or infancy. A boy who had crippling polio in a family too poor to buy a wheelchair. So, that boy had to crawl around on his belly and his mother had to lift and carry him as much as she could until he died as a teenager.

You’ll find a Lithuanian bootlegging kingpin named Joe Yucas, who was so powerful that he had protection from City Hall, and he had two young men, the Poskevicius brothers, killed in one night in his saloon.

We have a lady who lost two husbands in succession to the mines. There is a charismatic criminal named “Hunkie John,” John Buskiewich. Actually, that’s a story I had to leave out of my book because the third-wave Lithuanians who were reading my blog posts said, “You’ve got so many Lithuanian suicides, murders, bootlegging. Can you please not make Lithuanians look like criminals all the time?” So one of my best stories is only on the blog. And that is “The Ballad of “’Hunkie John,’” who became a heartthrob to dozens of local flapper girls in 1925 when John went on trial for second-degree murder committed during the armed robbery of a roadhouse.

John had had a wretched family life growing up, but whenever he entered the courtroom for his trial, he would greet his supporters like a celebrity. And after he was convicted, he managed to break out of jail. Before he exited, he hit the button to open all the other cells. And when he was running away, he never got farther than a couple of blocks because he decided to stop and see his girlfriend. That’s his story, and the newspapers would call immigrants or Eastern Europeans “hunkies” (a slur, like dago, mic, or wop) back then.

In addition to relying on my volunteer genealogy researchers, Tom Mann and Bill Cellini, Jr., I did a lot of online newspaper searches. Springfield’s State Journal-Register, being a paper of record for the state capital, was a great source. But because “news is negative,” that certainly skewed toward crime and punishment any research that did not involve the Knights of Lithuania, St. Vincent de Paul Church, or veterans and war casualties. Yet, I have to say that with 2000 Lithuanian immigrants in a city of 50,000 back then–to have three unnatural Lithuanian immigrant deaths in just a 12-day period in February 1926, to me, seems disproportionate.

And yet, I don’t want to overemphasize the “wildness” of the first wave or stereotype all its members like the newspapers did back in the 1910s and 1920s. I want to make sure that everybody knows that there was a less visible core of very good people, family people, who really crawled up out of their former lives of degradation in Lithuania or built on the progress made by their immigrant parents. And through hard work and faith and community self-help, these first-wavers achieved an impoverished respectability, and then their families even reached the middle class, particularly as dangerous, dirty industries declined and more white-collar jobs became available in state and federal offices here. So there eventually was a success story, and maybe assimilation is the coda, the final chapter of that story.

Sigita Balzekas: Before we close, Sandy, you must talk about the most famous Lithuanians from Springfield briefly in case someone doesn’t know.

Sandy Baksys: Well, Senator Dick Durbin is the number two man in the dominant party in the Senate, which is the Democrats. He’s from East St. Louis, but he has lived in Springfield since the early seventies. My older sister used to babysit for his children when they were toddlers. His first house in Springfield was a block from where I grew up.

Sigita Balzekas: I would say Rep. John Shimkus, too. He was a Republican representative in Congress.

Sandy Baksys: Yes. Dick Durbin and John Shimkus both played a leading role in founding the Baltic caucuses in the Senate and the House of Representatives in the Congress. They both represented my area here in Springfield—there was a strong conjunction of Lithuanian political power here for several decades. John Shimkus is actually from Collinsville, but the way his district was drawn, he represented the neighborhood where I grew up and where my dad still lived through the 1990s and early 2000s.

Sigita Balzekas: Wonderful. Well, Sandy, I can’t thank you enough. Truly, you’ve shared some terrific insights. And I just realized something. I identify as a displaced person’s child, but my paternal grandfather did come to the United States and did make it into the coal mines of Pittsburgh, only to return to Lithuania to tell my father, “Never immigrate to the United States because you might end up in a coal mine.”

Let me briefly thank our sponsors, the members and donors of the Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture and the Illinois Arts Council, as well as the City of Chicago, Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events.

And thank you, again, everyone for coming, and we look forward to seeing you again. I hope you’ll join us on other occasions.

Sandy Baksys: Thank you, Sigita.

Sigita Balzekas: Thank you.

11 Thursday Nov 2021

Posted in Sandy's Blog

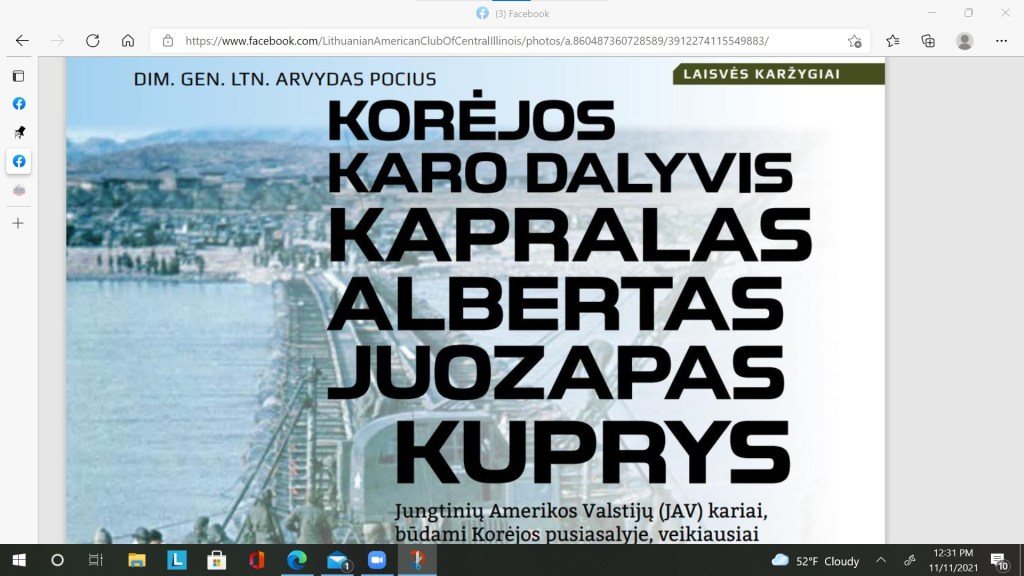

Recently, retired Lithuanian Chief of Defense Arvydas Pocius learned he once had a cousin from Springfield, Illinois, who had served in the Korean War. Lt. Gen. Pocius honored his deceased cousin Al (Albert) Kupris of Springfield in the July 2021 issue of Lithuania’s Karys (Warrior) magazine. Our friend Vida Totoraitis translated the article (below) into English.

Korean War Soldier Corporal Albertas Juozapas Kupris

By Retired Lt. Gen. Arvydas Pocius

Karys (Warrior) Magazine

July 2021

Many Americans today know little of the war fought by American soldiers on the Korean Peninsula. In America, this conflict that occurred between two tragic, much-better known wars (World War II and Vietnam) is often called “The Forgotten War.”

Yet even though war was never officially declared by the USA, tens of thousands of solders from the USA and other countries, under the banner of the United Nations (UN), participated in defending South Korea. The aim was not only to protect the country, but also to stop the spread of communism from the Soviet Union (USSR) and communist China.

An official peace treaty between the warring sides was never signed and that’s why, even today, there is still a “de facto” state of war between the two Koreas, North and South. American soldiers are still stationed in South Korea to defend its freedom and independence, and that’s why it’s important for us, still today, to understand this history and to remember those who served, including those who are serving even now.

The story of this “Forgotten War” reminds me of the novel “The Alchemist” by the popular Brazilian writer Paolo Coelho. The main character in the book abandons his village and sets out on a quest for his “life’s treasure.” Traveling all over the world, he experiences a whole range of adventures and dangers. Not finding what he was looking for, he ultimately returns home and then, unexpectedly, near the ruins of his childhood church, his long quest is finally fulfilled.

Relatives

As readers of Warrior Magazine already know, since 2012 I’ve undertaken the initiative to search for our Lithuanian countrymen (compatriots) spread around the world who have taken part in wars or military operations on behalf of their diaspora countries. The stories of American soldiers of Lithuanian descent who served in the US Army were published first in Warrior Magazine, and then in 2014, in a collection entitled, “Knights of Freedom.” In 2020, a second edition of the book “Knights of Freedom” published the stories of diaspora soldiers who had served in the armies of the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia.

Continuing my research through the labyrinth of the Internet, I came across information on my father’s maternal cousin, Albert Juozapas Kupris, who lived with his parents in Springfield, Illinois. I was surprised to learn that Albertas had served in the U.S. Army in the Korean War, something we relatives in Lithuania had never known. Understandably, during the period of the Cold War between the USA and the USSR, it was not permitted to write about military service. Nor did my modest cousin Albert ever mention it.

Albert, his wife Rita, and their son Albert Joseph Kuprys, Jr. (Kuprys became Kupris in the USA) traveled to their ancestral Lithuanian homeland in May 1993 after its restoration of national independence. They even traveled to Skuode and saw the mill on Albert’s ancestors’ land. However, by that time, because of the death of Albert’s mother Vincenta Maceviciute, the bonds between the two branches of the family had long been broken (so we did not meet).

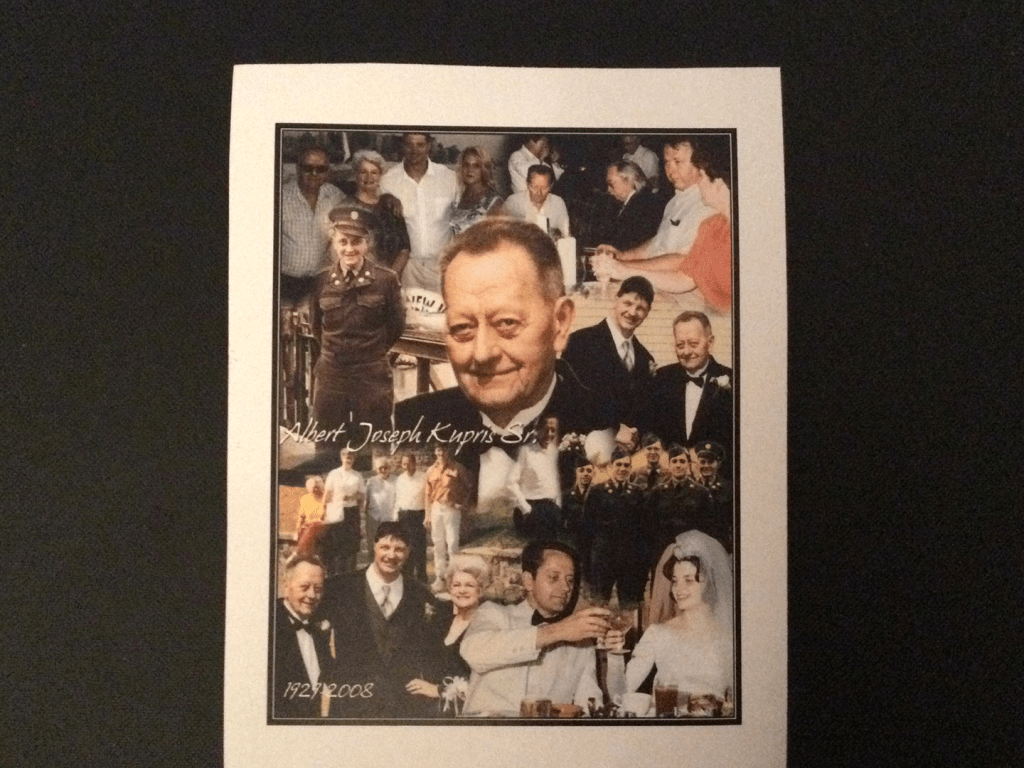

Albert’s mother Vincenta was the sister of my father’s mother Ona Maceviciute. They were born in Rusiupiu village in the Skuodo district of Lithuania. There were a total of three brothers and six sisters in the family. In 1928, Vincenta, being 19 years old, married a much older man, Albinas Kuprys, the son of a well-to-do farmer whose family owned a mill near Skuode. Six months later, the couple went to live in Springfield, Illinois, where in April 1929, their son Albertas Juozapas Kuprys (Sr.) was born.

The parents baptized him at St. Vincent de Paul (Lithuanian) Catholic Church, to which Albinas already belonged. In Springfield, Albert attended Catholic grade school. He played basketball on his Catholic boys high school team and learned to play the violin and concertina. Later, he even entertained at various Lithuanian events, such as weddings. In 1947, after graduating from high school, Albert got a job at Springfield’s Sangamo Electric Company, where he was certified as an equipment operator. He worked at this factory for more than 31 years.

In the Korean War

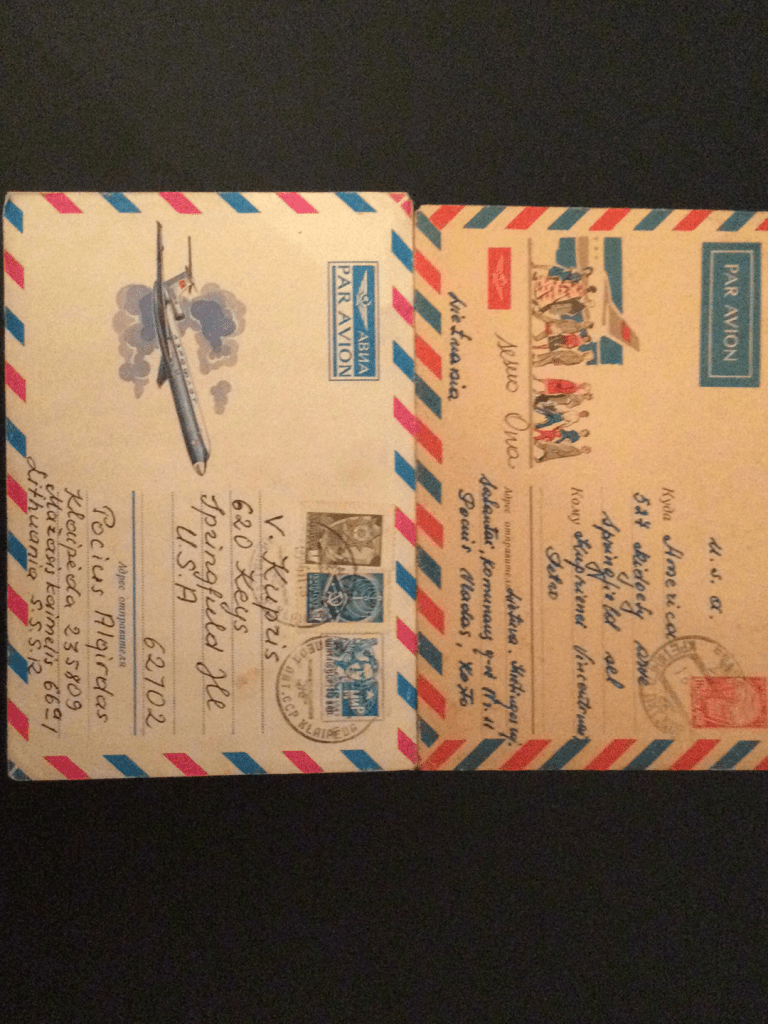

During the Cold War between the USA and the USSR, sisters Ona and Vincenta Maceviciute only took the risk of writing to each other on special occasions. Interestingly, Albert’s wife Rita still has, in her possession, several well-preserved examples of this correspondence, which she sent copies of to me while I was searching for material about Albinas, Vincenta’s husband. These copies of the sisters’ correspondence included several envelopes mailed from Soviet-occupied Lithuania.

In 1951, with the start of military conflict on the Korean Peninsula, the USA decided to plunge into the fight in order to defend this war-torn country, already ravaged by the Japanese during WWII, against further invasion by the communist USSR and China. The US government instituted a military draft and Albert was called up to serve in the U.S. Army. Due to his civilian expertise, he was assigned to an engineering unit.

Albert completed a course on war engineering in Missouri, and after several months of basic combat training, he was deployed to the Korean war zone. There, he served for 11 months, seven days on active duty.

After his Korean mission, he was transferred to active reserve and assigned to the 5th Army 574 mission unit (GCED Granite City, Ill.). He remained in the active reserves for five years.

In a letter about her husband, Rita Kupris writes that in her youth, just after marrying Albert, she took an interest in his Army service. However, he did not reveal much, only that he had been called up at about the same time that he became a specialist at Sangamo Electric. He did convey to Rita that he did not regret his military service and was proud that he had done his duty with honor. He also described how he had taken special courses in infantry combat and military engineering to prepare for his mission in Korea. He never complained of the hardships there.

When Rita wanted to find out more about her husband’s wartime impressions and experiences, he would answer that American commanders had forbidden soldiers from talking about them. However, a few weeks prior to his death (Albert had cancer and died from complications of surgery), Albert, with tears in his eyes (which in 39 years of married life Rita had very rarely seen), finally began to talk about his service in the Korean War.

With great emotion, he related to Rita how the North Korean communist soldiers did not provide aid to their own wounded soldiers on the battlefield and also failed to bury their dead.

These facts notwithstanding, with great sorrow, Albert then told his wife that his best friend had died by his side in battle, and that there had been no way to immediately retrieve his body due to the need for retreat. That image of his friend’s abandoned body, even though it was later retrieved and buried with honors, had remained in Albert’s mind all the rest of his life, his most lasting impression of the war.

During the Korean conflict, US Army engineers had encountered many obstacles due to the country’s climate, terrain, and poor transportation infrastructure, and this was a real hindrance to the US and its United Nations allies. In fact, the complicated terrain often enhanced the enemy’s advantage in massive surprise attacks.

The Army’s engineering units, including Albert’s, countered the enemy’s advantages and its ability to launch surprise attacks by blowing up important bridges and lines of communication to put the brakes on the enemy’s movements. This often provided the time necessary for UN soldiers to regroup and reinforce defensive positions, even to create substantial defensive lines.

Because Albert took part in actual combat, in addition to military engineering, he was presented with the U.S. Army Combat Infantry Badge, as well as the U.N. Medal and Korean Service Medal with Bronze Star.

Albert died Jan, 7, 2008 and was buried with honors in the Camp Butler National Cemetery near Springfield with the participation of the Sangamon District Military Burial Group of veterans. This contingent included representatives of all branches of U.S. forces. A bugle played taps, the traditional melody dedicated to the memory of fallen warriors.

Rita Kupris says that after the ceremony, she met with a veteran who had been a friend of Albert’s while both served in Korea. According to the friend, everybody in their company had held Albert in high esteem. Unfortunately, after their military service, Albert and the man had never met again.

At the end of her letter to me, Rita Kupris acknowledged that it was very difficult for her to write her remembrances of her not so long ago departed, beloved husband. She said that as memories filled her heart with love, esteem, pride, sorrow, and loneliness, tears had filled her eyes. However, Rita said, she had ultimately found pleasure in re-visiting Albert’s photos and service documents—and great gratitude for the blessings of such a long married life with such an amazing man.

18 Wednesday Aug 2021

Posted in Sandy's Blog

25 Tuesday May 2021

Posted in Sandy's Blog

When Mrs. Ann (Tisckos) Wisnosky worked in the Old State Capitol downtown (during its tenure as the Sangamon County Building), she could never have suspected that her son Augie one day would be the resident architect on the massive historical renovation of Springfield’s most monumental Lincoln-era building.

From 1966-68, Augie was resident engineer on site for the architectural firm Ferry Henderson. He supervised the dismantling of the historic Old State Capitol stone by stone, saving and storing each of those external stones, building offices and parking underground (where the Illinois State Library is now located), and then rebuilding the interior to resemble the way it looked during Lincoln’s time.

Although Augie must have known about Abraham Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech at the Old State Capitol, he couldn’t have known that the grand historic site would later host the presidential campaign announcement of President Barack Obama in Feb. 2007, or the announcement of Obama’s choice of running mate, then-Senator Joe Biden, in August 2008. History-making in front of the old capitol’s massive columns undoubtedly continue well into the future…

To learn more about Augie’s on-site management of the Old State Capitol restoration, which was commemorated with a plaque and ceremony in April 2018, please listen to his oral history at http://www.oralhistory.illinois.gov

To read more about Augie’s immigrant family history, seehttps://lithspringfield.com/2014/06/07/an-immigrant-childhood-ann-tisckos-wisnosky/ and

https://lithspringfield.com/2014/11/23/bankers-to-lithuanians/