In February 1913, Illinois State Journal-Register columnist Octavia Roberts made and wrote about a visit to St. Vincent de Paul Lithuanian Catholic Church. Her “Through Feminine Eyes” column gives us our best eye witness account today of what first-wave Lithuanian immigrants looked like 100 years ago.

Sunday mass at the church was packed, with people standing in the aisles and in front of the vestibules, some of them for a full two hours (a longer mass than most of us have ever endured). Men and boys sat on one side of the church, women and girls on the other. It’s not surprising to read that, according to Roberts, the “majority had blue or gray eyes,” and “were a handsome, sturdy people.”

The writer makes much, indeed, of the men’s thick and wavy hair. Although she doesn’t say, I imagine the congregation she observed that day was uniformly young. Elders with balding pates–uncles. aunts, parents and grandparents–had mostly been left behind because the light at the end of the immigrant’s tunnel back then could only potentially be reached through a lifetime of hard, manual labor—impossible for the old or weak. “As for the women,” Miss Roberts writes, “their pretty hats covered up their faces according to the mode of the year.”

Lithuanian married women’s head-dress. Courtesy of Reflections from a Flaxen Past, by Kati Reeder Meek.

She goes on to marvel at “how well-dressed” the female Lithuanian immigrant was after invariably arriving in America “in a full skirt with waist of contrasting material worn in her province, with her head tied up in a bright handkerchief and her goods in great square of cloth, knotted at the corners.” Remarkably, “in an incredibly short time,” these immigrant women “would put away the clothes of the old country and be dressed in the latest fashions of America.”

Lithuanian woman’s holiday “costume,” courtesy of Reflections from a Flaxen Past, by Kati Reeder Meek.

Putting on the New

I like this passage on many levels. Probably the most important meaning is only hinted at: That before coming to America, Lithuanian immigrants knew only homespun clothing in a cash-poor economy where you didn’t wear it, use it, or eat it unless you grew it or made it yourself. According to Roberts’ article, prior to immigrating, most Lithuanian men were poor, landless agricultural workers (on large estates) earning only about $30 a year. Women no doubt had even less, if any, cash, and it was their job to spin all the family’s clothes from flax, a little cotton, and lots of wool.

It hardly takes much imagination to conceive of these immigrant women’s excitement at being part of a town economy where families had several hundred dollars a year, and retail options for spending it. Since their cash was still far from sufficient, immigrants still made, not bought, much of what they needed, including cultivating most of their own food, just like in the old country. Critical, non-cash subsistence skills still made the difference between success and failure.

But the habit of having at least one set of store-bought clothes for Sunday mass, for those who could afford it, was likely a habit carried over from the home country, only to be more fully expressed when economics made that possible. And you can bet that one or two fine and fashionable Sunday outfits would have seemed like a necessary dividing line between the old life and the new–at the very least to show that all that had been left behind–given up–was worth it. That they were moving forward in life.

As for St. Vincent’s well-dressed immigrant ladies the day Roberts visited, once married, none was permitted the public exposure of singing in the church choir. That meant the female choir Roberts observed in early 1913 was composed of the few, small girls too young to marry in a culture where the girls married young. However, if this photo dated that same year is correct, due to its pastor’s efforts, St. Vincent’s had an adult mixed-voice choir only months later, perhaps composed of unmarried adult women or women with their husbands. (By the 1920s, it was one of the finest church choirs in the city.)

Homespun to ‘Home Clothes‘

One of the last things my homespun-wearing, subsistence-farming Lithuanian father did before fleeing the advancing Russians in 1944 was to bury his store-bought Sunday suit and shoes in a cardboard box– never doubting, of course, that he would return. (Our grandmother’s china dishes are also still somewhere underground on our lost Baksys land–musu jame.)

Dad’s homespun customs, which I never understood growing up, were echoed in our family’s pronounced distinction between “home clothes” and school or church attire. Before we were of the age when we could take more control over our personal appearance, this went beyond formal vs. informal or school vs. play. Until I was 7 or 8, Dad wouldn’t even let his daughters wear pants in the winter or shorts in the summer–his rule for girls was dresses, no matter what the other kids wore.

I also still remember, as a kindergartener, the shame of being ambushed in my “home clothes” when a neighbor boy unexpectedly packed his birthday party with our classmates in full party dress. And, I still think, to this day, that our family’s “immigrant” difference was most firmly established in my mind by our clothes, and our reaching, as girls, for a normalcy and belonging that was always just out of reach–through clothes that were also always somehow just out of reach.

Clothed in Dignity (and Glory?)

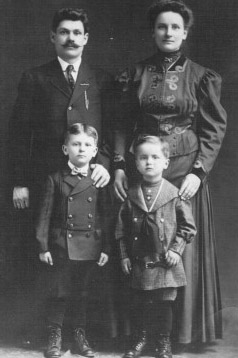

I’m sure others have noticed that poor Lithuanian coal miners and their wives always seemed to take amazingly glamorous “portrait” photos. I puzzled for years over this apparent discrepancy between what I knew about the economic status of my Great Aunt Mary Yamont (or Marija Baksyte Jomantiene) and her coal-mining husband, Benedict, Sr., and their full sartorial splendor in a family portrait in 1908 or 1909.

It seems improbable that all of our ancestors somehow made and lost millions by the time we met them. And even if true in some cases, great reversals of fortune could hardly explain the pure number of photos wherein glamorous immigrant dress seems to belie verbal histories of poverty. Doubtless these photo portraits aimed to show families at their most solemn, dignified and successful.

Also, in true poverty, limited photographic resources would hardly be wasted on papering the world with that era’s version of the goofy Polaroid snapshot—or today’s proliferation of digital “selfies.” To the contrary, it actually seems logical to me that poverty, itself, and trying to make “bella figura” to the people back home, can explain the extravagance of early 20th Century weddings and other high photographic occasions that were exceptions to the daily grind of hard, manual labor.

I’ve even heard that photographers traveled with glamorous wardrobes to entice the poor to become temporary poseurs to wealth. And, what better than a photograph to render wistful permanence to a dead-ended miner or laundress’s unfulfilled dream of ease and luxury—never to become real in this life?

Lithuanian Sunday church, their own church that was like a piece of their own home soil, was also a place to dream, and to begin to self-actualize, with the support of community and the many social clubs and Lithuanian Catholic lay societies. Fr. John Czuberkis spoke to columnist Roberts of organizing a larger mixed choir, sports and drama clubs.

Pastor of St. Vincent’s during the parish’s peak years for growth and membership (1909-1919), Father C. knew what a different, more fully human identity meant to his parishioners, even if that was achievable only at Sunday church–or on special occasions, for example, when the men donned the full regalia of the “Vytautas, Grand Duke of Lithuania Society.”

It’s interesting to ponder what role the individual public statement–and group reinforcement—of Sunday costume likely played for people who had shed so much, and were in the process of clothing themselves anew, in every sense of those words. I’ll bet Ms. Roberts, the writer, never knew her visit to St. Vincent’s would inspire such a meditation on the social meanings–and the elevating power of clothing–100 years later. My thanks to Tom Mann for finding and sharing Octavia Robert’s article from 1913.